R. Paul Wilson On: The Fake Chip Collateral Scam

Late night in Las Vegas, in a dark corner of a quiet bar, a discussion becomes heated until it is calmed down by a simple compromise.

But when the three parties go their separate ways, one of them has unknowingly lost (at least) a thousand dollars.

In a world where scams make real money with mundane ideas, I was surprised to hear that this old swindle was still circulating with a fresh (and clever) coat of paint and while it’s certainly rare, it’s out there.

The Set Up

The story goes like this:

A group of ‘businessmen’ are looking to recruit players who have clean accounts and player profiles at casinos around town and are offering to trade high value casino chips for cold cash with a 20 percent bonus for every stack they trade.

So for a $100 chip, the ‘businessmen’ will pay $120 in cash.

For $1,000, they’ll pay $1,200.

The only question you should be asking is: “Why?”

The Story

Reasons tend to fit a certain profile and so do the characters making this type of offer.

Whether it’s a possible mobster, gang member or drug dealer; a dodgy stockbroker, a crooked dealer or casino employee and even card cheaters looking to clean their cash, but all these setups have the same apparent objective: To launder money without setting foot in an actual casino.

So whatever the story, their reason for not spreading their cash in person is that they might be recognised or are wanted by the law and so on, and this will make sense and help ease any suspicions of a potential mark.

Here’s the hook:

We have large denominations of cash that need to be cleaned. We need players who can increase their chip buys but retain a large portion of high value chips over a month and then exchange those chips at an attractive profit.

With a few dozen players, we can run millions of dollars a year through casinos more safely than doing it ourselves and even with a 20 percent loss, we’d be making more than running our cash through other methods and sources.

All you need to do is bring us $10,000 a month in black chips and we’ll trade those for cash that’s untraceable and you can do with that whatever you want.

A common question might be: “If you don’t go into the casino, what are you going to do with the chips?”

The answer is simple and easy to believe when a mark is falling for the bait: That they have other people who cash out and deposit funds into accounts they control and it’s impossible to trace those funds back to where and who the cash originally came from.

The Meet

Somewhere far from the Las Vegas strip, away from electronic eyes, the scammers meet their mark to exchange chips for cash – but there’s more than one potential customer at the table.

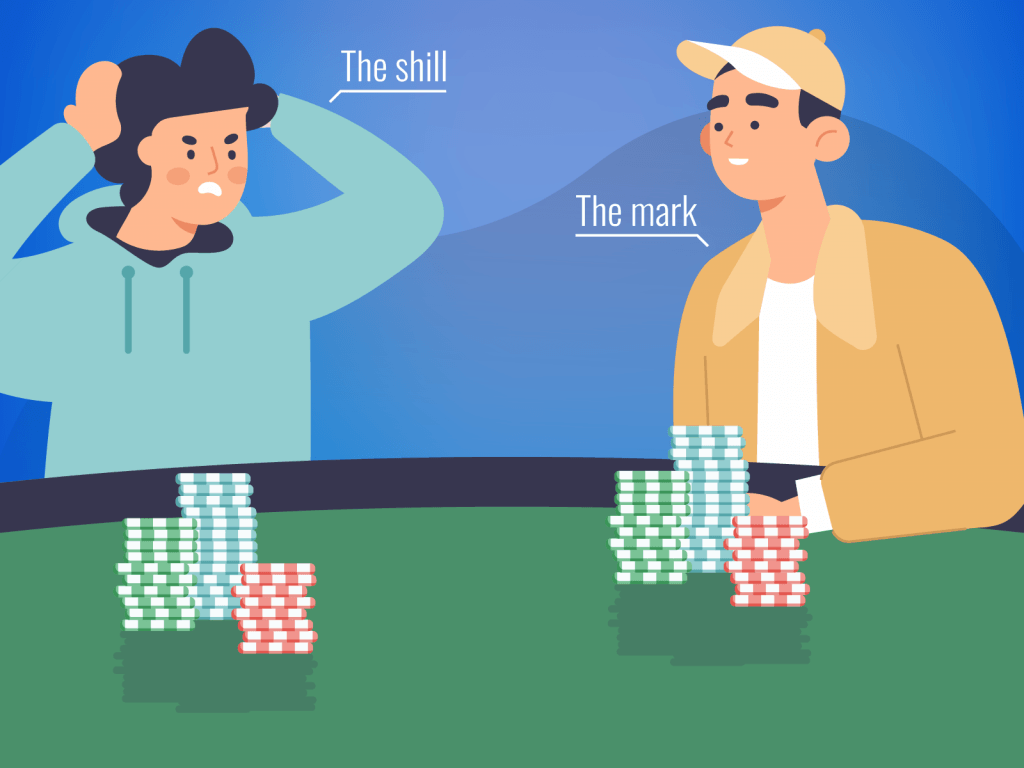

The mark has been made an offer to enter into an exchange that nets a healthy profit, but this deal is clearly not legal so in order to meet the man he or she will do business with, and to verify that the deal is real, he is invited to a late-night meeting where a second ‘player’ is in the bar at the same time.

When the mark arrives, this ‘other player’ joins them, supposedly to take advantage of the same deal but when they each present their chips, the shill has a lot more than the mark.

The second ‘player’ offers the mark a degree of comfort; that he’s not alone in this proposition but even better, the second player has some hard questions for the man who’s buying chips and isn’t shy about asking.

Why don’t you do this yourself?

How do we know this cash isn’t fake?

What are the limits on how much we can exchange?

Naturally, the answers to all these questions are aimed at satisfying the mark’s suspicions which creates a simple and powerful effect on that person.

When we challenge someone directly, we tend to be more contrary or suspicious but when we are separated from this challenge (as an observer) we are more likely to listen (and believe) the response.

A psychologist might debate this or explain it with a bucket of $50 phrases but as someone who has used this ploy hundreds of times during real scams, I can confirm that employing a shill to dispel expected suspicions is a well-proven and powerful tactic.

The tip off for this scam is actually a subtle one: The scammers tell you where to play and buy chips.

The Twist

The role of the ‘other player’ is more than just a shill in this case.

In fact, they’re critical to the outcome of the scam since they will motivate everything that’s about to happen.

The second ‘player’ acts more suspicious and may even accuse the mark of being part of a scam to trigger a natural response to prove their honesty, which makes them even easier to manipulate as the scam proceeds.

But the second ‘player’ has also brought a lot more chips than the mark so when everything is counted on the table, the apparent money-laundering ‘businessman’ tells his shill and the mark that he only has enough cash to cover one of their stacks.

Immediately, the shill demands that his chips are covered since he brought more and after a little byplay, the businessman agrees to pay the shill and not the mark.

This is more than just theatre, it’s a test.

If the mark drives headlong into this argument and demands that they’re paid instead, there’s an excellent chance of taking that mark for much more than $1,000 (which they were instructed to bring in black chips from a particular casino).

This is an important step since it tells the scammers whether or not to rip and run or play their victim for more money.

The Sting

So, what happens?

The shill gets paid off in cash, with a 20 percent profit that leaves the businessman without enough cash to pay the mark, so his chips are returned with an invitation to meet up tomorrow night and complete the transaction.

This is also a blow-off if the con artists will have read the mark as being too suspicious or too unpredictable to play for more, which is doubtless the real objective of this con game.

If the mark is insistent and clearly hooked by the idea, there’s a real possibility they might bring $10,000 instead of just $1,000, in which case they would be allowed to return home with the same chips they brought to the bar with instructions to buy $9,000 more with their hard earned money then lose it all thanks to a bait and switch at the same bar.

But even when a mark is too difficult or isn’t worth playing, the con artists can still walk away with a $1,000 thanks to a devilishly simple switch of the mark’s real casino chips!

The Switch

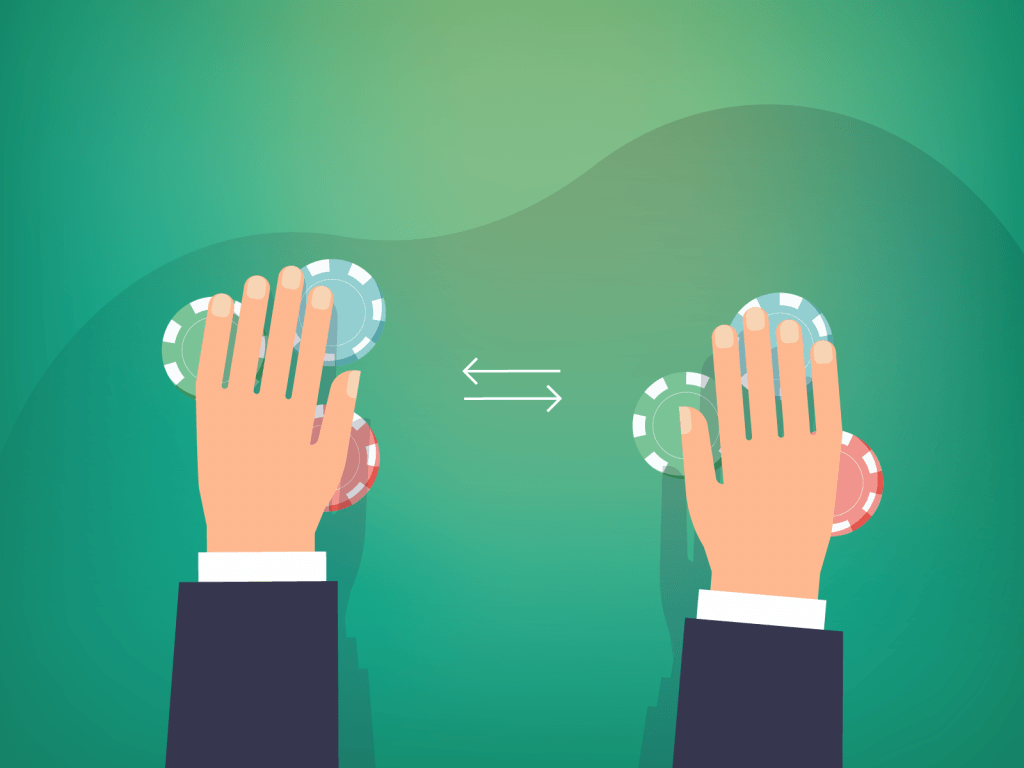

The switch is what we call a ‘non-move’ and (from the story I heard) seemed to go like this:

The mark’s (real) chips are counted, then the shill’s (fake) chips are counted and stacked alongside.

After the discussion (or argument), a stack of fake chips is simply passed back to the mark from the combined stacks.

Unless the mark is particularly suspicious, this will work every time thanks to the delay caused by the shill’s questions and demands.

If the hustlers are extra smart, they might use a little added misdirection to adjust the stacks at some point, moving a stack of fakes to the position previously occupied by the mark’s real chips.

Later, the scammer would apparently take the mark’s chips and return them but even this is unnecessary if the mark is completely convinced that all the chips are real.

The Blow Off

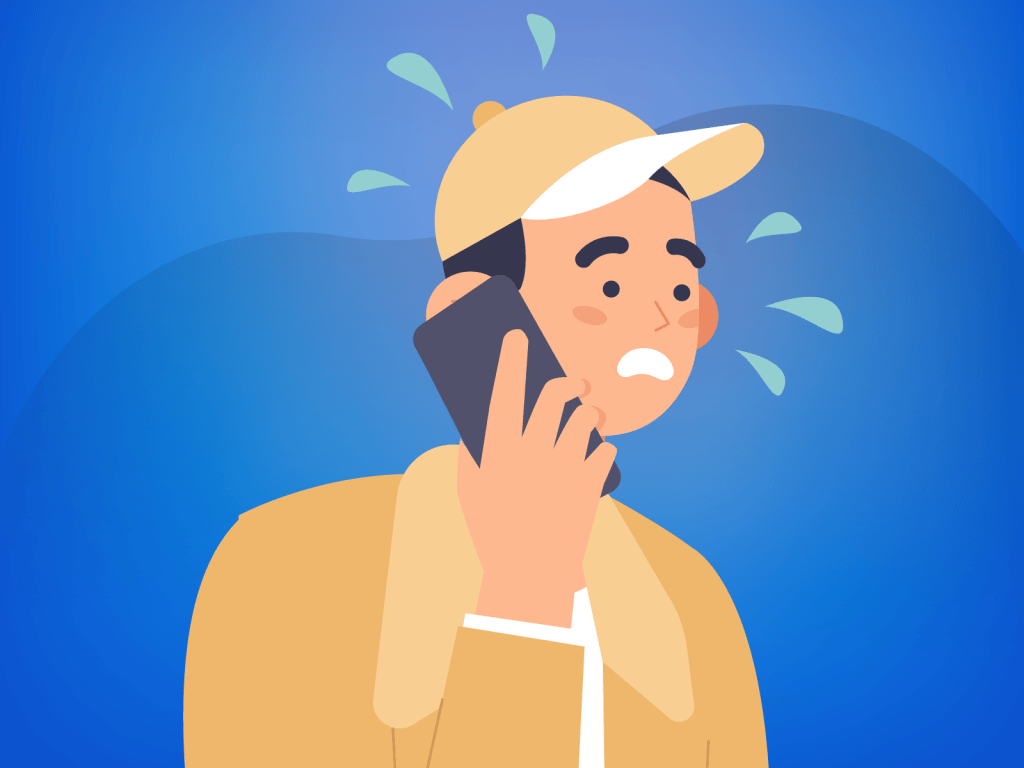

This was the clever part and it surprised me at first but makes complete sense.

On returning home, the mark receives a call from the businessman, accusing him of being in on a scam with the other player and telling him all the chips are fake!

Sure enough, on closer examination, the chips they returned home with now look a lot less convincing and the mark is now the owner of $5 worth of rebranded house chips.

The beauty of this deception is that the mark has nowhere to turn to report the crime.

He or she cannot go to the police because they were obviously taking part in a crime themselves!

And they can’t go to the casino because they would immediately be under suspicion there too.

Best of all (from the hustler’s perspective) the fake chips are never revealed to the casino who would no doubt investigate further.

That’s the beauty of the blow off – it stops the mark from finding out they have fake chips at the cashier’s desk and causing the casino to investigate further.

The Lesson

This scam is a simple test to see if someone will take bigger bait but when it doesn’t work, they still lose a lot of money to the scammers.

So what happens if the mark takes the bait and returns with 100 black chips?

Well, it could go several ways from a straight steal to a clever switch of chips or cash when the exchange is conducted – perhaps in the car park from the trunk of a car, which has proved to be an excellent location to switch entire bags or suitcases in the past.

A clever (but nasty) strategy would be to swap the cash for a duplicate bag filled with cheap drugs mixed with innocent powder but just enough that the mark would panic and never report anything to the police.

How it ends is less important than how the scam begins – with a believable story designed to hook a likely mark, then take them on an expensive rollercoaster ride.

The harsh truth is that if you get involved with something that is clearly illegal, you’re most likely just a bucket of chum in shark infested waters.