R. Paul Wilson On: Currency Exchange Scams

It seems that western countries are accelerating towards cashless societies where every payment or transaction might be monitored or tracked by entirely benign and friendly government overseers.

But in the gambling world, cash remains a powerful tool for managing one’s bankroll, tipping staff, or sharing profits away from prying eyes.

Sure, crypto offers some financial anonymity while also being in the sights of authoritarian regimes that would prefer some control over whatever monetary tools are used within and without their borders.

But for most offline transactions, cash is still king and there are countless scams to be wary of in your travels.

I Need A Guy Who Knows A Guy

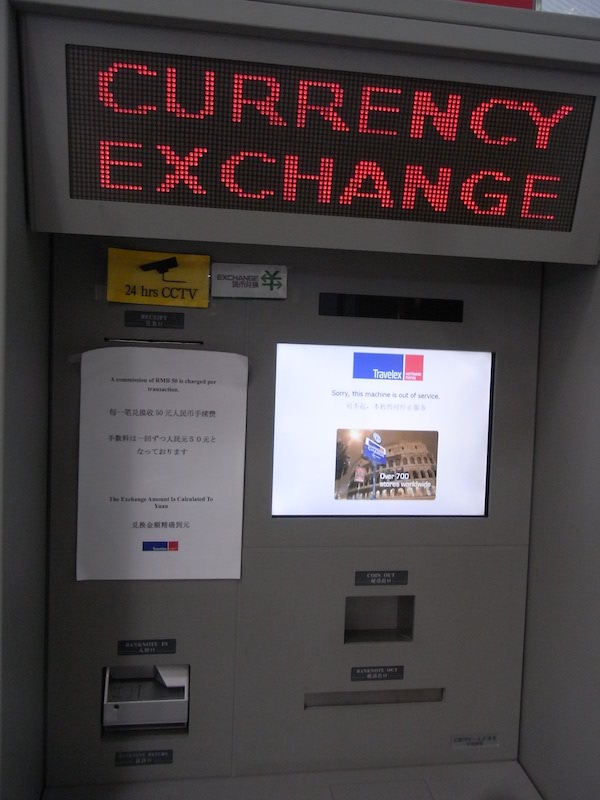

Exchange rate cons are so common that anyone who travels regularly will know where to find them, which is often at a “legitimate” bureau de change in airports or tourist hotspots.

In Paris, these money changers are everywhere and appear to compete with each other while their rates or fees make all of it a wash in terms of being a sh*tty deal no matter where you go.

Unless you happen to be a Parisian who knows a guy who knows a guy – who knows another guy.

During a profitable visit many years ago, I found myself with a lot of cash that would need to be changed before returning home, but I quickly balked at the exchange rates and fees being offered around the city.

Luckily, my friend and host was also a frequent traveller and drove me to a little office down a back alley and up some stairs near a side street in an obscure part of the city.

I couldn’t find that office again for love nor money but on that day, I saved a large chunk of change for the price of lunch and a few card tricks between friends.

Ever since, I’ve always asked local contacts where the “place” is to change money and am often lucky to find someone with a guy who knows a guy who knows another guy.

In Macau, we changed our cash at the cage in several casinos; in Tokyo, a local friend navigated Japanese rules and paperwork to get me the best deal while in Ho Chi Minh City.

A friend visited a little apartment where his cash was whisked away for 10 worrying minutes until an old lady returned with fresh dollar bills that his local contact carefully checked before completing the transaction.

Herein Lies A Problem

The risk in each of these situations is that you could easily be entering into a scam where you can be robbed or ripped off with counterfeit cash so in each of these cases, I (or my friends) relied on a trusted local contact who knew “the lay of the land” in terms of fraud and deception.

I’m not saying that theft doesn’t happen in Tokyo but there are clear signs whether a business or a procedure is legitimate and in Paris, my friend was too important a guy and too smart to be taken in by (or to facilitate) this type of con game, so I had confidence in that scenario.

In Macau, the casinos change money easily and regularly so long as the cash (and the person carrying it) isn’t criminal and they offer better rates than one would find at home, presumably to keep some of that cash on their tables.

But an apartment in Vietnam with strangers taking the money away before they exchange it?

No thanks.

Cash can be dangerous for all sorts of reasons, so when moving it around and changing currency we all need to be careful that a familiar method in one location doesn’t expose you to scams in another.

So sure, my friends and I tend to ask trusted local contacts where to find better deals but if there’s any doubt – any at all – I’d rather line up behind the tourists to get robbed by a clerk with a calculator.

Counterfeit Exchanges

Across Europe and in many parts of the world, fake exchange offices attract transient victims to lose money either through bad arithmetic, counterfeit cash, or outright theft.

In many cities an office isn’t even necessary.

In Prague, for example, bogus money traders prey on tourists near legitimate (though ridiculously expensive) currency exchanges and approach people claiming to be from an exchange with preferable rates.

The scam is simple since it’s easy to spot someone checking posted exchange rates, highlighting that they must be carrying cash and are therefore worth scamming!

So once a likely target is spotted, the hustler knows they are ripe (worth taking) but also what they want and are actively searching for at that exact moment in time.

Knowing what someone wants is the con artist’s most powerful advantage and in this scenario it can be all too easy to leverage this information into a quick and easy deception.

All the scammer needs to do is cut into the tourist before they approach the exchange desk and give them a story with promises of a better rate and no fees.

Needless to say, many people are quick to jump at that “opportunity”.

The twist (in Prague) is that these counterfeit currency converters do not trade people’s cash for Czech Crowns but for expired Belarusian Rubles that appear similar to foreign eyes and are (of course) completely worthless.

Around the city, you can see signs warning people not to exchange money on the street.

But human beings are often victims of their own impulses, which scammers know how to trigger using centuries-old psychological tricks that never fail to manipulate people in the heat of the moment.

And it’s not just exchange offices where these scammers prey upon the unwary.

At ATMs, clever con artists wait for travellers to withdraw cash, spotting anyone who receives large denomination notes, such as 2,000 CZK, then offers to break their bill in exchange for four 500 CZK notes that are actually – you guessed it – expired Belarusian bills.

Familiar Territory

As with many con games, being unfamiliar with a city or country means you might be easy prey for this kind of “fish out of water” con so care must be taken in any cash transaction on foreign soil but also at home.

In the UK, I was once approached in the waiting area of a bank with a proposition to swap cash since I had dollars and they had pounds; the logic being that the bank would only take a chunk of our money when we could both save by exchanging directly.

My “swindler sense” told me immediately this was too well practiced a pitch to be trusted so I turned down her “kind” offer and sure enough, before reaching the counter she left the bank to find another sucker.

How common this is inside banks I can’t say but while financial institutions can cost more in terms of fees or less attractive rates, going off-reservation requires a lot of trust and an unknown degree of risk.

Lead image: Donald Trung/Wikimedia Commons