VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: Atomic Testing in Nevada Ended by the 1960s

Posted on: April 5, 2024, 08:04h.

Last updated on: April 22, 2024, 09:55h.

EDITOR’S NOTE: “Vegas Myths Busted” publishes every Monday, with a bonus Flashback Friday edition. Today’s entry in our ongoing series originally ran on July 24, 2023.

Director Christopher Nolan’s movie, “Oppenheimer,” throws a spotlight back onto the era of America’s nuclear weapons testing. The biopic explores physicist Robert Oppenheimer’s role in developing the world’s first two atomic bombs.

Following the detonation of those bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which led to Japan’s surrender and the end of World War II, the US government began test-exploding new nuclear weapons at the Nevada Test Site, now called the Nevada National Security Site, near Las Vegas in 1951. This created the phenomenon known as “atomic tourism.”

Most people believe the era of nuclear testing came to an end sometime in the 1960s. Or in the ’70s. Or surely by the ’80s. However, atomic bombs were exploded just 65 miles northwest of the Las Vegas Strip up to 1992.

“That’s a common misperception among our visitors,” said Joseph Kent, director of curation and exhibits for the Atomic Museum, a private national museum operating in Las Vegas since 2005 under the 501 (c) 3 nonprofit Nevada Test Site Historical Foundation.

Why don’t more people realize that the federal government was still exploding nuclear bombs a stone’s throw from Vegas three years after The Mirage opened?

Because atomic testing, much like prostitution in Las Vegas, went underground.

Truth Bomb

The January 1951 detonation of a nuclear warhead at the Nevada Test Site, then called the Nevada Proving Grounds, was the first of 100 similar explosions in the air over the 1,355 square-mile plateau, which was carved out from the Nellis Air Force Gunnery and Bombing Range.

“The site was chosen because it was a lot cheaper to have one site where the national labs developing these weapons could bring them,” Kent said. “And it made sense logistically because Las Vegas only had about 25K residents back then.”

The biggest atmospheric test was Operation Plumbbob in 1957. That blast packed 74 kilotons, or 74K tons of TNT, which equaled five Hiroshima bombs.

“The goal really was to make the weapons more efficient and powerful, but at the same time, test smaller weapons that could hit specific targets,” Kent explained.

Operation Teapot, a series of 14 explosions conducted in the first half of 1955, measured how houses, household items, food, shelters, metal buildings, equipment, and mannequins (standing in for humans) survived at various distances from a blast.

Nuclear Attraction

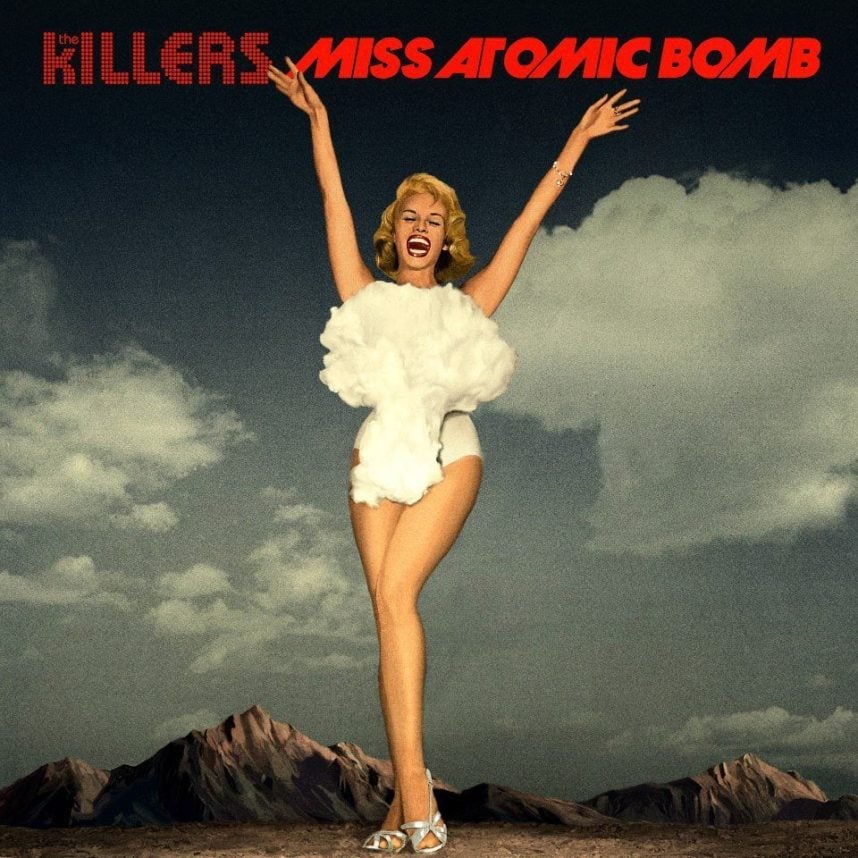

The mushroom clouds rising over the Nevada desert, one every three weeks or so, proved a spectacular tourist attraction. Visitation surged as Las Vegas nicknamed itself “the Atomic City.” Copa Room showgirl Lee Merlin posed in a mushroom-cloud swimsuit and was photographed as “Miss Atomic Bomb.” Even the famous “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas” sign, erected in 1959, employed the atomic-age design style known as Googie.

“In the early ’50s, the bomb captured the imagination of the American public,” Kent said. “Everything from company logos to TV shows were atomic-themed. An episode of ‘I Love Lucy’ showed Lucy prospecting for uranium.”

Though the US provided no information about the type of weapons being tested, the tests themselves were hardly top secret. The Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce printed calendars listing detonation times, suggested viewing locations, and scheduled viewing parties. The Sky Room at the Desert Inn hosted a popular one. So did Virginia’s Café downtown, which rebranded itself the Atomic Café in 1952 and added a rooftop bar for blast viewing. The Atomic Café is now the oldest free-standing bar in Las Vegas.

Watching from Las Vegas was deemed safe at the time, though a $100 million compensation package offered by the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act of 1990 to all residents of nearby Nevada, Utah, and Arizona able to link cancers and other diseases to their exposure to the fallout suggests otherwise.

As part of that package, scheduled to sunset on June 10, 2024, those who were downwind of the explosions can receive $50K each.

“I think people really go the extra mile to normalize things to make them less scary,” Kent said. “Let’s make it something fun and silly, so it doesn’t make it seem as scary anymore. If only people back then knew the consequences of what they were watching, it probably wouldn’t have seemed so thrilling.”

Underground Zero

After a while, the novelty of rising plumes of death wore off and atomic tourism fizzled. By 1963, with the Cuban Missile Crisis over, fears dwindled and the US, Soviet Union, and the UK signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty. This prohibited nuclear weapons tests in the air, underwater, and in space.

The treaty came as a result of the public becoming more aware of the dangers of testing,” Kent said. “There was a call for doing something different, either ceasing testing or finding a safer way to do it.”

The US performed 828 total underground tests at the Nevada Test Site. The reason this wasn’t common knowledge is because none of the tests produced a mushroom cloud or any fallout that anyone had to be alerted about, only the occasional ground rumble and some massive, still-existing on-site craters.

There was one huge, horrific exception. At 7:30 a.m. on Dec. 18, 1970, a nuclear bomb was lowered into a hole more than 900 feet underground and detonated as part of the Baneberry Test. About 300 feet from the hole, a crack opened in the ground, and a cloud of fallout shot 8,000 feet into the atmosphere, eventually settling over parts of Nevada and California.

“The Baneberry test resulted in an accidental release of radioactivity,” Kent said. “Like with most accidents, they learned from it and knew what to avoid in the future.”

Two of the workers with the highest levels of exposure contracted leukemia and died. After their widows spent years fighting for compensation, the courts found the federal government negligent but not liable. No damages were rewarded.

Tests Grounded

The underground tests ceased in 1992 because, by then, the Soviet Union collapsed and Congress passed a test moratorium in response to Russia’s announcing one first. The moratorium has been extended several times since, though the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty signed by the US, Russia, China, France, and the UK still hasn’t been ratified by a number of crucial nuclear players, including North Korea, Pakistan, and India.

Since 1992, the Nevada National Security Site has hosted counterterrorism and first-responder training, and has supported the National Security Agency’s Stockpile Stewardship program.

“Basically, they test components of the stockpile of weapons that the US has to make sure they’re safe, secure, and reliable because, over time, things change,” Kent said.

The site has also been the recipient of 13,625 cubic meters of radioactive material from Idaho, which the US government acknowledged last year.

While I can’t speak to that specifically, I can tell you that the NNSS has served as a safe and secure waste disposal option for decades, and typically accepts low-level waste that results from cleanup being done at DOE sites.”

Tours of the Nevada National Security Site can be booked at nnss.gov.

Look for “Vegas Myths Busted” every Monday on Casino.org. Click here to read previously busted Vegas myths. Got a suggestion for a Vegas myth that needs busting? Email corey@casino.org.

Related News Articles

VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: The Old MGM Grand Was Imploded After the Fire

VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: Actor Lee Marvin Shot Vegas Vic with an Arrow

Most Popular

Mega Millions Reportedly Mulling Substantial Ticket Price Increase

NoMad Hotel to Check Out of Park MGM on Las Vegas Strip

Most Commented

-

End of the Line for Las Vegas Monorail

— April 5, 2024 — 90 Comments -

Mega Millions Reportedly Mulling Substantial Ticket Price Increase

— April 16, 2024 — 9 Comments -

Long Island Casino Opponents Love New York Licensing Delays

— March 27, 2024 — 5 Comments

Last Comments ( 4 )

I went to the atomic testing museum right after it opened, with a main question in mind. Who thought it was a good idea to light off a thermonuclear weapon with a heat output of 11 times hotter than the surface of the sun? Didn't get a good answer from the scientist on site. Second question was, in a closed loop system, what is/was the feedback and backlash of all that released heat? He told me they didn't know I've been out at the nnss, xod recovery. I've seen the drums from Idaho. Refer to national geographic for the photos of area 5.

Yes, I was here in 1951. My father worked there and died of cancer in 80. Still waiting for the govt to admit it.

I only made it partway through the Atomic Testing Museum before tearing up

My father died because of theses testing. In fact I’ve lost my great grandpa, my great grandma, my aunts, my uncles cousins due to the nuclear testing that is in this movie. It’s called downwinders as a very serious cancer that affects multiple parts of your body. My father died of brain, lung, spine, liver and kidney cancer.