LOST VEGAS: 1969 West Las Vegas Riots

Posted on: April 1, 2024, 12:00h.

Last updated on: April 1, 2024, 01:17h.

Google “West Las Vegas Riots” and you’ll be shown stories about an uprising that erupted in the historically Black part of Las Vegas — in response to the Rodney King verdict in 1992. Though that tragic event cost one person his life, another riot in the same place 23 years earlier, was deadlier.

And it is almost completely lost to history.

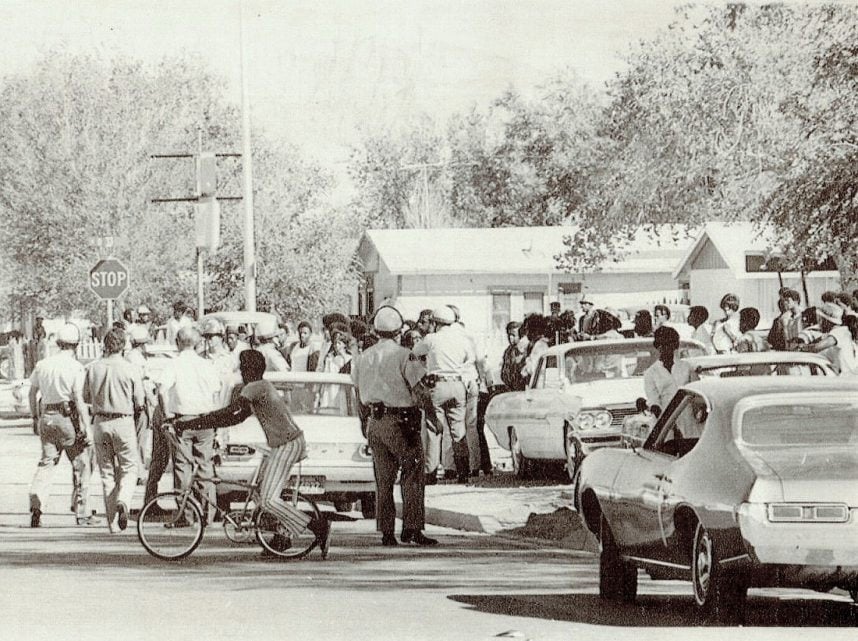

From Oct. 5-8, 1969, Westside residents set fires, broke windows, looted stores, and overturned parked cars in an event sparked by protests of police brutality against two Black men. By the time the smoke cleared, two people were dead, 200 arrested, and hundreds injured.

“This was the largest uprising in the city’s history at that time,” Tyler Parry, Associate Professor of African American and African Diaspora Studies at UNLV, told Casino.org.

So why are accounts of the riots not only absent from history books, but almost nowhere to be found on the internet?

Even though the Black community had a legitimate reason to contest the police state in the late 1960s, that’s just not something that people were sympathetic toward,” Parry said. “Because they saw it as just some rowdy teenagers out to destroy property at the time, most people just said, ‘Let’s just forget that and move on.’”

Information about the riots can now be found almost exclusively in old books or on paid newspaper archive websites. Parry ran across the Las Vegas Sun‘s newspaper coverage on microfilm at UNLV

“For my purposes, it is interesting to see it from the point of view of this historically voiceless population,” said Parry, who has made the riots the subject of a lecture he will give on April 4 at UNLV — part of its University Forum series.

What Started It

Parry, whose opinion is informed by hundreds of interviews, news reports, and private letters he uncovered, believes the riots were a product of growing racial tensions not only in Las Vegas, but across America, at the time.

“This was the conclusion to a decade that exposed the false promises of many political leaders,” he said. “It showed how people living in the post-civil rights era remained dissatisfied with the lack of progress and demanded the government’s attention by openly resisting police brutality and systemic racism.”

The spark for this particular episode of ugliness was a common traffic stop. A Black police officer, Robert Arrington, stopped a taxi driver, who was also Black, for speeding on Sunday, October 5.

Gerald Davis, who was on the street fixing his mother’s car, knew the driver and walked over to ask what was wrong. According to Parry, Arrington viewed this as “an affront to his authority.”

Arrington followed Davis back to his mother’s car, according to Parry, yelling “‘What did you say? What did you say to him?!’”

“The officer had no probable cause,” Parry noted. “There was no reason for Davis to be harassed. Legally, he didn’t have to talk to the officer.”

Trying to ignore Arrington, Davis walked inside his mother’s house. According to Parry, both officers followed him. Once inside, they saw him hand a gun, which was legally registered to him, to his sister.

“And that’s when it just kind of popped off,” Parry said.

Point of No Return

Arrington drew his weapon and instructed Davis to get on his knees with his hands up. When Davis’ younger brother, Mike, saw this, he walked outside the house with an unloaded shotgun.

As I understand it, he intended to exercise his Second Amendment right at what he saw as an abuse of state authority,” Parry said. “He was a hot-headed teenager who was probably tired of seeing police officers harassing people in his community.”

Arrington followed the brothers back into the house and arrested them both, according to Parry, but not before macing everyone in the house.

By this point, a crowd of about 150 people had gathered to watch what was happening.

Within a few hours, a full-on standoff was underway between 200 police officers and an equal number of protestors at the Golden West Shopping Center around the corner. Police, realizing that their presence only made matters worse, pulled out shortly before midnight.

By the next morning, city officials were holding their breaths, hoping to brand this an isolated incident.

But that afternoon, two white men driving into the shopping center were attacked by a gang and beaten unconscious, igniting a second wave of violence. Rioters looted a Friendly’s for liquor bottles to make Molotov cocktails. They tossed them, as well as rocks, at all police cruisers entering the neighborhood.

A 64-year-old electrician was then pulled from his vehicle and beaten while a woman was yanked out of hers and forced to strip.

More than 150 helmeted police officers and sheriff’s deputies responded by locking down, and then repeatedly sweeping through, 40 square blocks in an unsuccessful bid to regain the upper hand.

Las Vegas Mayor Oran Gragson imposed a 7 p.m. to 6 a.m. curfew and declared a state of emergency, asking Gov. Paul Laxalt to mobilize the National Guard. By nightfall, the power company shut off all electricity to the area.

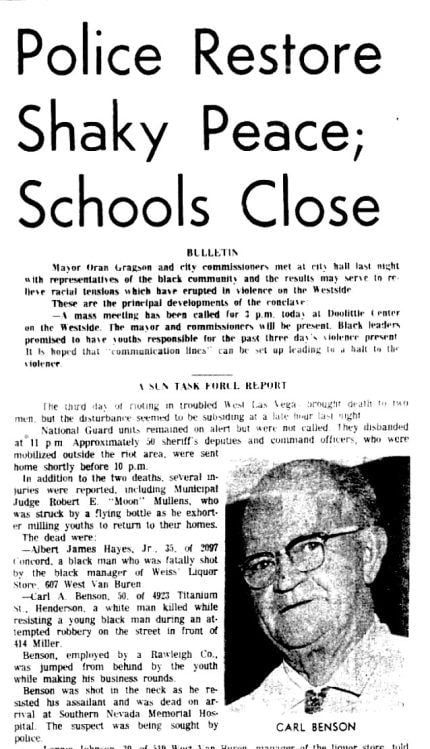

The third night was when both fatalities occurred. Albert Hayes Jr., a 35-year-old Black man, was fatally shot in the back by Lonnie Johnson, the Black manager of a liquor store who heard the store’s window smashed and saw Hayes running from the building.

Also on October 8, Carl Benson, a 71-year-old white man, was fatally shot in the neck while resisting an attempted robbery of his W.T. Rawleigh Co. delivery truck. George D. Singleton, 22, was charged with his murder.

Though more than 350 guardsmen assembled at their armories, they were never deployed. The riots petered out on their own, leaving the Westside in ruins.

American History X-ed

According to Parry, the African-American history of Las Vegas has been subverted, only until recently, “in favor of its mob history and Howard Hughes and the corporate takeover of the casinos.”

The type of history that deals with money has historically been more interesting to people when they think about Las Vegas,” he said. “So what happened in the Westside has never really been prioritized in the broader narrative. To this day, most people who come to Las Vegas don’t even know that there’s a historically Black section of town, even though it’s literally right across the railroad tracks.”

Parry will present “They Forget, We’re People Too: Revisiting the 1969 Uprising in West Las Vegas,” from 7 p.m. – 9 p.m. Thursday, April 4 in UNLV’s Beverly Rogers Literature and Law Building, Room 101. Admission is free to the public.

“Lost Vegas” is an occasional Casino.org series featuring remembrances of Las Vegas’ forgotten history. Click here to read other entries in the series. Think you know a good Vegas story lost to history? Email corey@casino.org.

Related News Articles

Las Vegas Casino Cyberattacks: A Timeline

LOST VEGAS: The Original Las Vegas That No One Knows About

Most Popular

Mega Millions Reportedly Mulling Substantial Ticket Price Increase

NoMad Hotel to Check Out of Park MGM on Las Vegas Strip

Most Commented

-

End of the Line for Las Vegas Monorail

— April 5, 2024 — 90 Comments -

Mega Millions Reportedly Mulling Substantial Ticket Price Increase

— April 16, 2024 — 9 Comments -

Long Island Casino Opponents Love New York Licensing Delays

— March 27, 2024 — 5 Comments

Last Comment ( 1 )

Iwas a student at las vegas high the first race riot i remember started there at a homecoming football game rancho lost and a group of students from rancho mouthed off and the fight was on from Vhs all the way back to Rancho high lasted hours .it was the first problem i remember with race as a factor .