Treasury Report Highlights Casino Money Laundering Risk

Posted on: June 18, 2015, 03:18h.

Last updated on: June 18, 2015, 03:18h.

The US Department of Treasury has published its annual National Money Laundering Risk Assessment report, a 100-page document focusing on the threat that money laundering may pose to the US financial system.

This year, casinos get a whole chapter to themselves, which is perhaps unsurprising when you consider that, in 2013, some 27,000 Suspicious Activity Reports (SARS) filed with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) related to casino transactions. Forty percent of these were in casinos in Nevada or Atlantic City.

But it’s what doesn’t get reported that most concerns FinCEN.

“Casinos are primarily destinations for recreation and entertainment, not financial services,” warns the report, “which may lead some casinos to unintentionally or inadvertently put customer service against Banks Secrecy Act compliance.”

This is why casinos sometimes fail to file Currency Transaction Reports on transactions over $10,000, as required by law, the report suggests, because they are unwilling to ask for intrusive personal details, especially when it comes to high-rollers, their best customers.

Since the passage of the Money Laundering Control Act 1986 it has been a requirement for all US financial institutions to file a CTR to FinCEN for any currency transaction over $10,000.

Dirty Money

The far most common form of “money laundering,” according to the report occurs within Nevada sportsbooks, which are often used by illegal out-of-state bookies and illegal online gambling sites to make wagers to help them balance their odds.

Also common is “minimal gaming,” in which customers buy chips or deposit funds with a casino and then cash out after little or no play; a strong indication of money-laundering.

The report cites numerous instances of financial foul play; there’s the North Carolina tobacco farmer who sold contraband cigarettes to criminals for resale in Canada, and plowed his ill-gotten gains into the slot machines at an Indian casino before receiving a casino check for the credit balance.

Then there’s the Arizona man who solicited $4 million in funds claiming a gambler’s insider advantage, which he then used for gambling in Vegas while converting it into cash for his own use.

LVS’ $47.4 million Wrist Slap

There are high-profile cases too, such as that of the Las Vegas Sands Corp and the Chinese-Mexican drug dealer, Zhenli Ye Gon.

In 2014 LVS was forced to settle for $47.4 million with federal authorities to avoid prosecution after it permitted Ye Gon to wager $84 million at the Venetian. He was arrested in 2007 and stands accused of international drug trafficking.

LVS admitted it failed to properly scrutinize the source of Ye Gon’s funds.

There’s also the case of the Tinian Hotel & Casino and Casino in Northern Mariana Islands, a US dependency which last month was fined a record $75 million for violation of anti-money-laundering regulations. The casino was indicted for failing to file thousands of CTRs.

Of particular concern to Treasury was the expansion of US casinos abroad, which can allow a person to establish a casino account in one country and then access it in another.

“The most significant money laundering vulnerability at US casinos is the potential for individuals to access foreign funds of questionable origin through US casinos,” it concludes, “and to use the money for gambling and other personal or entertainment expenses, and then withdraw or transfer the remaining funds either in the United States or elsewhere.

Related News Articles

Pair Found Guilty in New Zealand Roulette Scam

Adelson Dealt Blow in “Foul-Mouthed” Libel Case

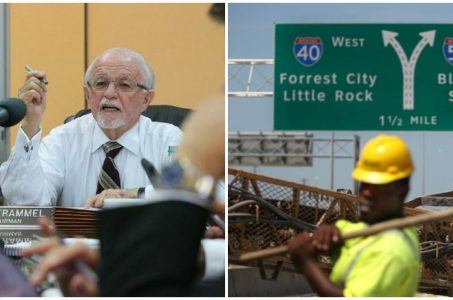

Arkansas Highway Commission Cautions Voters on Casino Ballot Question

Most Popular

Mirage Las Vegas Demolition to Start Next Week, Atrium a Goner

Where All the Mirage Relics Will Go

Most Commented

-

Bally’s Facing Five Months of Daily Demolition for Chicago Casino

— June 18, 2024 — 12 Comments

No comments yet