Gaming to Return to Historic Moulin Rouge in Vegas — For 1 Day

Posted on: April 4, 2024, 11:58h.

Last updated on: April 4, 2024, 09:09h.

The experience itself won’t be much –- taking a few spins on a slot machine in a trailer on a vacant lot littered with broken glass and loose cement. But the bragging rights to having gambled on the former site of the historic Moulin Rouge are certain to draw hundreds of people to 840 W. Bonanza Road in Las Vegas during one day next month.

On Wednesday, the Nevada Gaming Control Board (NGCB) made the recommendation to issue a slots-only, one-day nonrestricted gaming license to the current owners of the Historic Westside landmark.

If, as expected, the Nevada Gaming Commission (NGC) approves the request on April 18, then United Coin Co. will open a 40-foot shipping container containing 16 slots on the site for eight hours beginning at 6 a.m. on May 14.

This somewhat stilted display of commitment is required by state law, every two years, to preserve the property’s gaming rights. Nevada stopped issuing such licenses in the 1990s, so they’re highly coveted. And so far, the Gaming Commission has yet to deny the always-repeated request.

Why the Moulin Rouge Mattered

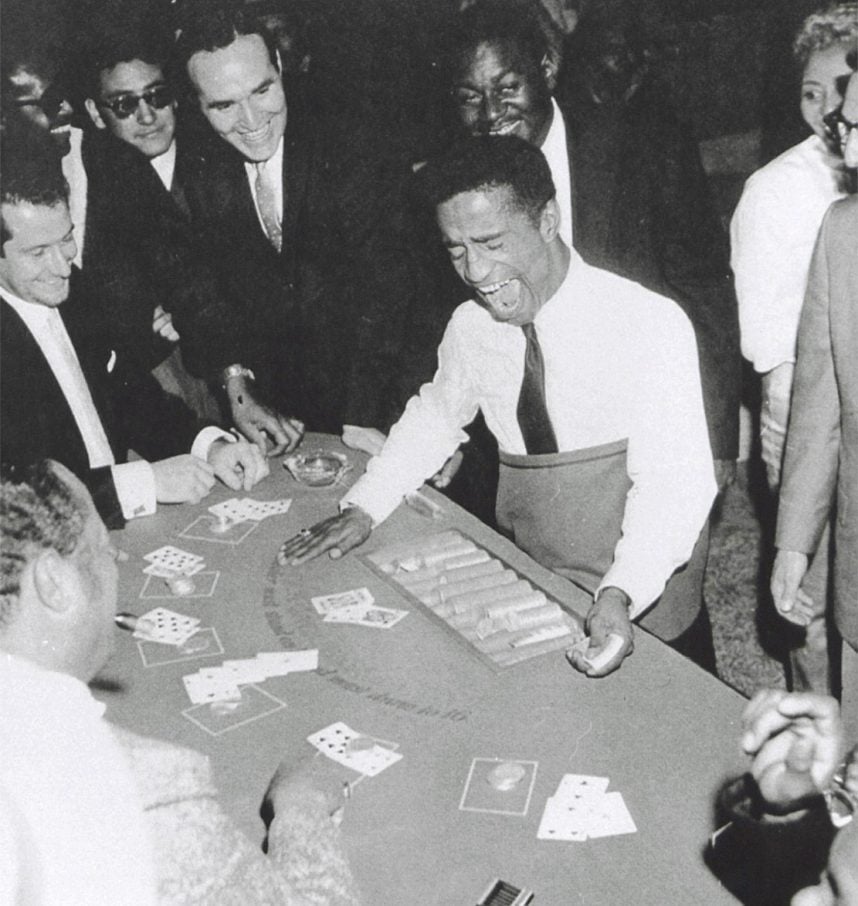

On May 24, 1955, the Moulin Rouge became the first racially integrated casino in the US.

Before either downtown Las Vegas or Las Vegas Strip casinos would allow African-Americans to gamble or work front-of-house jobs, the Moulin Rouge served as party central for Sammy Davis Jr., Pearl Bailey, Lena Horne, Count Basie, Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and their white friends and admirers, including Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland, and Jack Benny.

Unfortunately, the casino closed less than six months after opening. Though financial mismanagement, not racism, was officially to blame, it’s often correctly pointed out that racism prevented its struggling founders from obtaining bank loans as easily as their Strip counterparts could have.

The Moulin Rouge even made history five years after it closed for good. That’s when it hosted a 1960 meeting between casino representatives, government leaders, and the NAACP that ended segregation in all of Las Vegas.

At this historic summit, which became known as the Moulin Rouge Agreement, the casino reps reluctantly agreed to allow African-Americans to patronize their establishments and hold public-facing positions in them.

This landmark decision eventually led to bans on real estate redlining and discrimination in all employment and business licensing.

Sad Fate

Even its addition to the National Register of Historic Places in 1992 couldn’t save the Moulin Rouge from vandalism or a series of fires that eventually required what remained of the structure to be razed in 2010.

In 2020, Nevada-based RAH Capital paid $3.1 million for the 11.3 empty acres, including the parcel attached to an active nonrestricted gaming license, and agreed to assume nearly $2 million plus interest in liens associated with a site cleanup.

RAH has announced no current plans to develop the property. Despite a cavalcade of claims through the years about rebuilding the historic casino on the site, the money required to do so has never materialized.

Related News Articles

Remembering Suzanne Somers’ Vegas Years

VEGAS MYTHS BUSTED: Las Vegas is the World’s Gambling Capital

The Strange Parallels Between Fontainebleau and a Bygone Vegas Casino

Most Popular

Casinos That Were Never Casinos

Most Commented

-

End of the Line for Las Vegas Monorail

— April 5, 2024 — 90 Comments -

Mega Millions Reportedly Mulling Substantial Ticket Price Increase

— April 16, 2024 — 9 Comments -

Long Island Casino Opponents Love New York Licensing Delays

— March 27, 2024 — 5 Comments

No comments yet