LOST VEGAS: The Hoover-Damned Town of St. Thomas

Posted on: April 11, 2024, 07:00h.

Last updated on: April 11, 2024, 09:46h.

The human remains uncovered by the receding waters of Lake Mead claim the headlines, and rightly so. But they’re not the only secrets that climate change has forced the nation’s largest reservoir to give up.

Located on the northern reaches of what is now the Lake Mead National Recreation Area, about 60 miles east of Las Vegas, St. Thomas was once the most populated town in Southern Nevada. That was before it was intentionally drowned by the US government to fill Lake Mead.

Dead in the Water

St. Thomas was founded in 1865 by Mormon missionaries sent by their leader, Brigham Young, to start a settlement along the Muddy River in the Utah Territory (present-day Arizona).

The settlers chose a spot with fertile farming soil near the Muddy’s Overton arm, where it converged with the Virgin River to feed the Colorado. They built an irrigation system to grow their vegetable gardens, fruit trees, and cotton. They eventually intended to open a supply route to move that cotton back home to Utah along the Colorado.

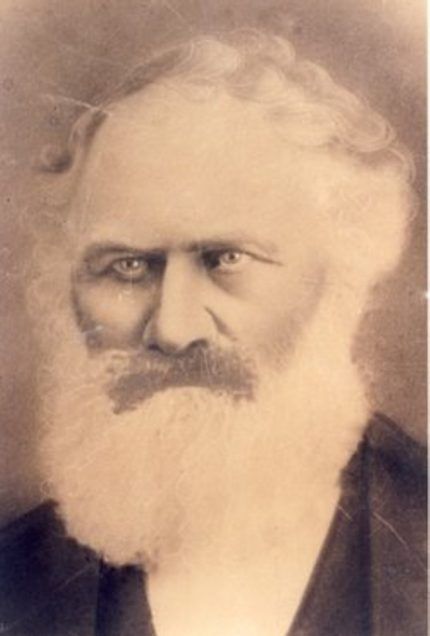

The leader of the settlement, Thomas Sasson Smith, quite immodestly conferred it with his first name. Smith, born in 1818, moved to Utah from his native New York State in 1848, four years after he was baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Many historical accounts blame the missionaries for settling in the Nevada Territory instead of the Utah Territory, by mistake. However, what really happened is that Congress redrew the Utah Territory’s western border in 1866, which rendered all Muddy River settlements a part of the relatively new State of Nevada.

The missionaries had no idea until an 1870 boundary survey determined St. Thomas to be in Nevada. Almost immediately, the state smacked the residents with five years’ worth of back taxes and fines.

In February 1871, with Young’s permission, the settlers abandoned their town and, not unlike the Mormons who first settled Las Vegas, high-tailed it back to Utah.

Only one man and his family remained. Daniel Bonelli operated a prosperous Colorado River ferry in Junction City (later Rioville), Nev., connecting mining towns in Nevada and Arizona. He also owned and operated the Virgin River Salt Company.

New Settlers on the Block

A fresh wave of settlers arrived in the 1880s, planting new crops and rebuilding St. Thomas into what historian James H. McClintock, in his 1921 record of the settlement, recalled as “a beautiful village.”

Townsfolk resided in 85 houses, according to McClintock, most on an acre of land featuring yards with rose bushes. Their streets were lined with shady cottonwood trees.

It was hardly ever a bustling city, but St. Thomas was at one point home to more than 500 people. It had its own school, post office, church, pool hall, auto garage, not one but two grocery stores, and an ice-cream parlor, Hannig’s, that boasted a soda fountain.

By 1911, St. Thomas was deemed worthy of a railway spur from Moapa station on the San Pedro, Los Angeles, and Salt Lake Railroad.

Once that began service, refrigerated railroad cars full of commercial goods, including food and much-welcomed blocks of ice, arrived regularly, immediately diminishing the need for local subsistence farming.

On their return trip, the railroad cars were packed with mined copper, silver, gold, and salt, which residents often traded for the goods.

St. Thomas even boasted a nice hotel, a 14-room lodge called the Gentry. Calvin Coolidge slept there while he was president!

And then, just like that, St. Thomas was gone.

Here Comes the Flood

It was Coolidge himself who gave the order to drown the town, signing the Boulder Canyon Project into law in 1928.

Was there something about his stay in St. Thomas he really didn’t like?

No. The need for a gigantic dam to tame the flood-prone Colorado, plus the added bonus of a reliable supply of cheap water and hydroelectric power for the growing Southwest, made the Hoover Dam seem impossible not to build.

And, the employment opportunities accompanying the dam’s construction continued the job started by the railroad in 1905 — of slowly transforming sleepy Las Vegas, population 5,000, into one of the Southwest’s biggest cities.

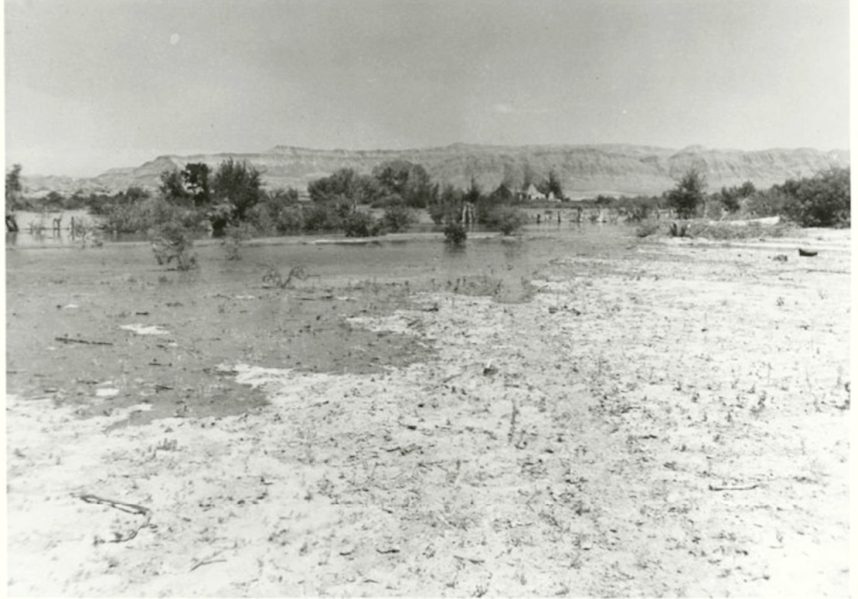

The US government seized all the land in St. Thomas by eminent domain, paying its residents minimally for their displacement. The flooding process began in 1935. Within five years, St. Thomas was under 50 feet of water.

At least the government had the compassion to relocate St. Thomas’ cemetery as part of its plan. It’s now in Overton, where today, the Lost City Museum employs a staff archaeologist to perform research into the history of St. Thomas and other Muddy River settlements.

Some St. Thomasites chose to dismantle and relocate their houses to Overton and other nearby towns. Others were less cooperative.

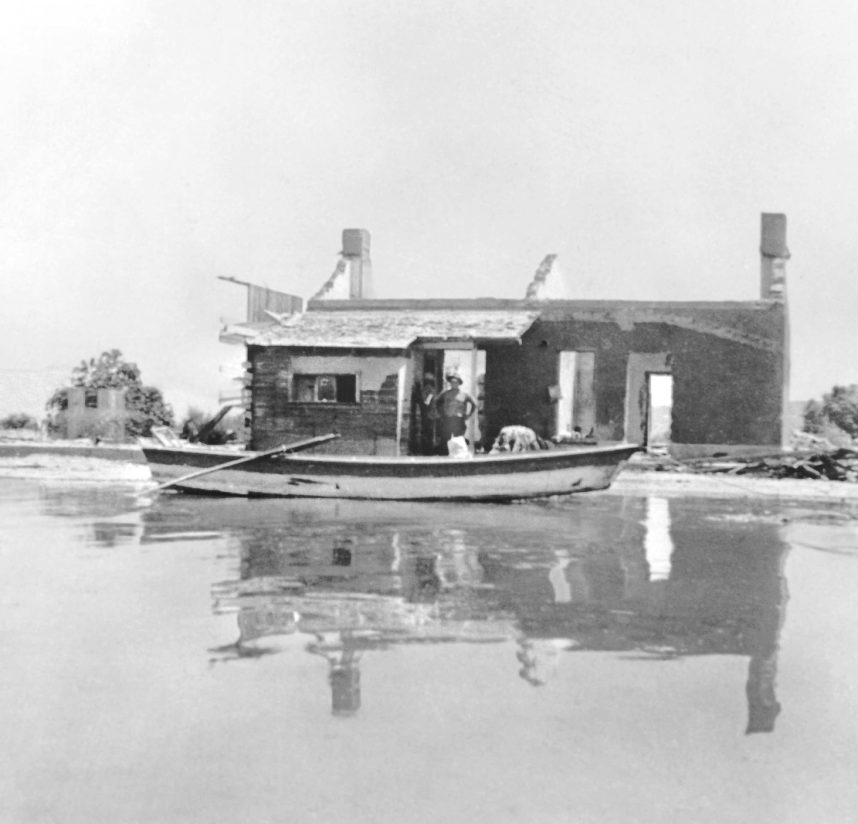

Such was the case with Hugh Lord, owner of the auto garage, who is credited with being the very last St. Thomasite to leave. Lord reportedly refused to believe that the rising new lake would ever reach his home.

When it finally did, on June 11, 1938, he rowed away from his house in a boat packed with his most cherished possessions.

According to author Aaron McArthur’s 2013 book, “St. Thomas, Nevada: A History Uncovered,” Lord lit his house on fire before rowing off, but that dramatic detail isn’t corroborated by most original accounts.

How to Find It

St. Thomas re-emerged during several droughts over the decades, most notably in 1945, 1965, and 2012. Reunions, attended by former town residents, were held during those years.

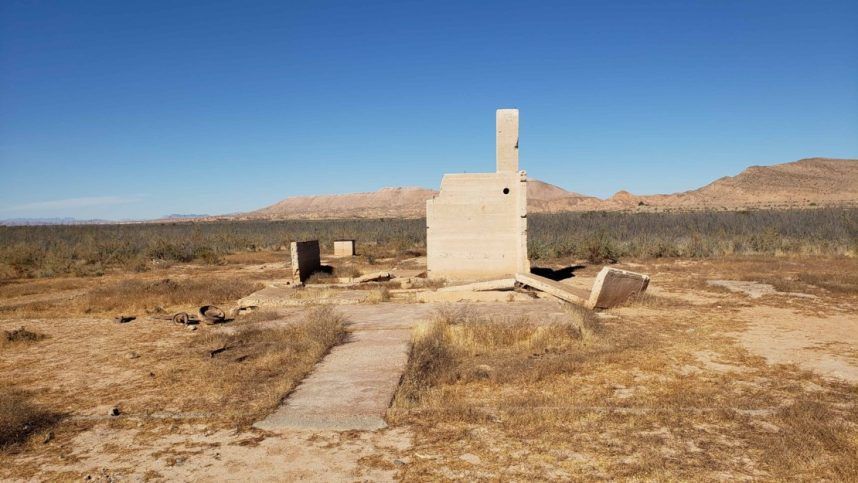

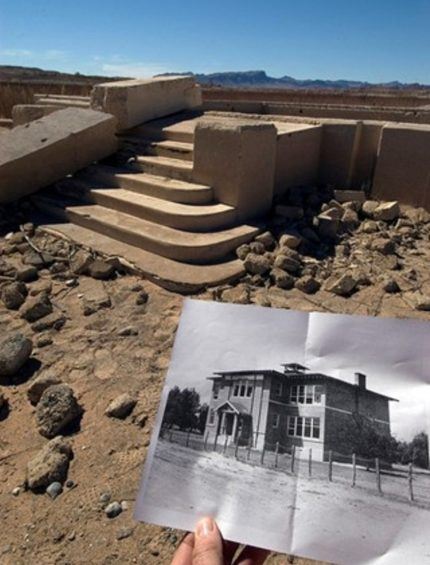

Now that more than 60% of Lake Mead is gone, St. Thomas has returned permanently, though the 80 years its buildings spent underwater have transformed them into scattered piles of foundations and nowhere-leading staircases.

Instead of water, what’s flooding the town these days are tourists. They walk a 2.5-mile loop trail through what remains.

The ruins of St. Thomas, protected by the National Park Service as a historic site, are best reached in a high-clearance vehicle with four-wheel drive.

A bumpy ride along a dirt access road, off Highway 169, ends at a parking lot. From there, follow the signs.

Lost Vegas” is an occasional Casino.org series featuring remembrances of Las Vegas’ forgotten history. Click here to read other entries in the series. Think you know a good Vegas story lost to history? Email corey@casino.org.

Related News Articles

The Buildings Elvis Presley Left in Las Vegas

Las Vegas Casino Cyberattacks: A Timeline

Most Popular

Mirage Las Vegas Demolition to Start Next Week, Atrium a Goner

Where All the Mirage Relics Will Go

Most Commented

-

Bally’s Facing Five Months of Daily Demolition for Chicago Casino

— June 18, 2024 — 12 Comments

No comments yet