LOST VEGAS: The Moulin Rouge

Posted on: July 25, 2025, 02:38h.

Last updated on: July 25, 2025, 04:35h.

Fifteen years ago today, wrecking crews demolished the tower and main façade of the Moulin Rouge casino on Las Vegas’s historic Westside. The property opened in May 1955 as the first racially integrated hotel casino in the nation. Yet casino didn’t live long enough to see the effect it had on changing social norms and public policy.

It closed only six months later.

Hall of Shame

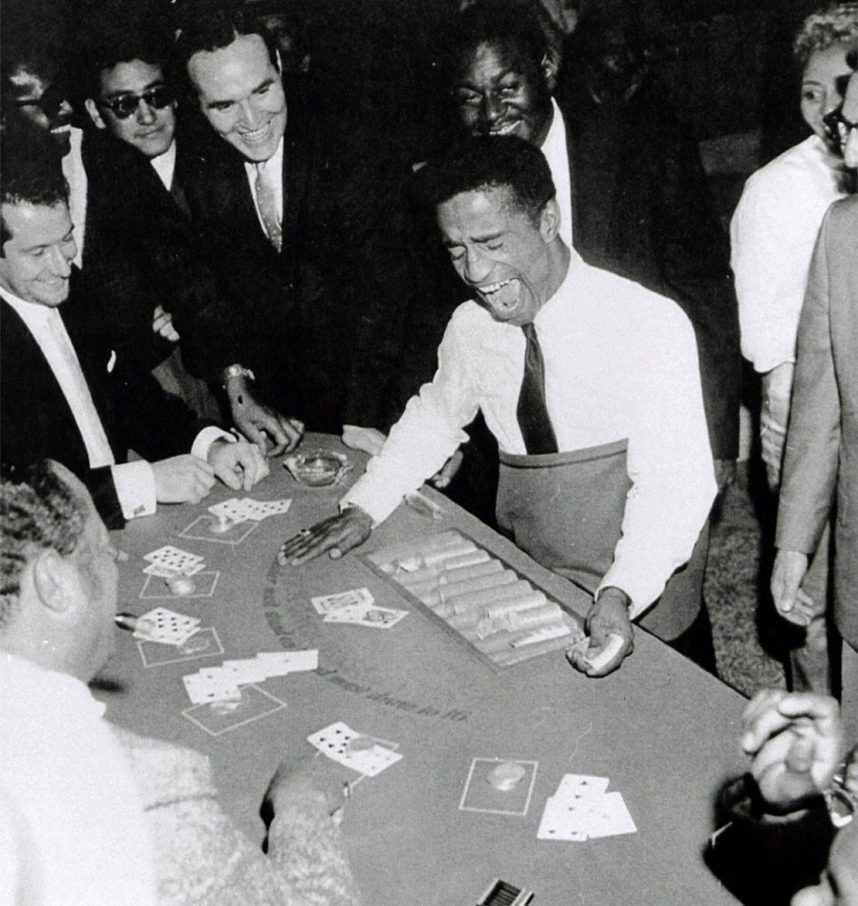

Las Vegas was a fully segregated city before the Moulin Rouge. People of color could work at Strip hotels, but only as cooks, maids, and janitors — “back of house” jobs where they went unseen.

They couldn’t even stay at the properties. This was true even of black headliners, including Sammy Davis Jr., Nat King Cole and Ella Fitzgerald.

A taste of how far we’ve come as a society is provided by this sentence about the Moulin Rouge, published by Variety in 1955: “This unusual spot continues to pull in the gambling sect, who are not alarmed in the least about rubbing elbows and dice in mixed racial company.”

The Moulin Rouge didn’t put an end to Las Vegas’ racist policies, but represented the official start of their dissolution.

It wasn’t until March 1960 that casino bosses — during a meeting with the NAACP and city and state leaders — reluctantly agreed to allow African-Americans to patronize their establishments and hold public-facing positions in them.

Inspired by the wave of civil rights activism sweeping the country, the NAACP had threatened a march on the Strip that would have embarrassed Las Vegas.

Fittingly, that meeting took place at the Moulin Rouge, which reopened just to accommodate what is known as the Moulin Rouge Agreement.

This landmark agreement eventually led to bans on real estate redlining and discrimination in all employment and business licensing.

Why It Closed

The casino hotel seemed a complete success, so why it closed is still a big question mark. Some historians point to unpaid debts or insolvency by its owners. Others blamed the mobsters who owned competing hotels.

Though blame isn’t usually placed on the racism of the day, it’s often correctly pointed out that it did prevent the casino’s struggling founders from obtaining bank loans as easily as their Strip counterparts could have.

The building stood for another 48 years, serving as a motel, a public-housing apartment complex, and finally, a flophouse. It made the National Register of Historic Places in 1992, but three fires — in 2003, 2009, and 2017 — gutted the already-crumbling structure.

After the casino’s tower was demolished in 2010, the rest of the ruins followed in 2017 — after more than 200 homeless persons were found living inside.

Today, nothing but the skeleton of its roadside sign remains. The building’s famous neon now burns on permanent display at the Neon Museum.

“Lost Vegas” is an occasional Casino.org series spotlighting Las Vegas’ forgotten history. Click here to read other entries in the series. Think you know a good Vegas story lost to history? Email corey@casino.org.

No comments yet