LOST VEGAS: The Lounge Act

Posted on: February 11, 2026, 01:38h.

Last updated on: February 12, 2026, 04:47h.

- High-energy lounge acts provided the 24-hour soul of the 1950s and ’60s Las Vegas Strip

- Louis Prima and Mary Kaye transformed small lounge stages into top-tier entertainment destinations

- Lounges became one of the first Las Vegas institutions killed by corporate math

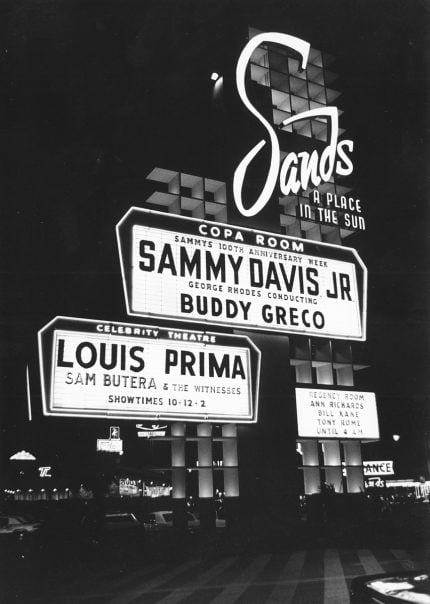

In the golden Las Vegas era of the 1950s and ’60s, the main showrooms were for the stars, but the lounges were the soul of the Strip. While headliners like Sinatra and Liberace performed polished 60-minute sets to 500–1,000 people at the Copa Room at the Sands and the Strip’s other main stages, the lounges featured high-energy acts that played from dusk until dawn for audiences of only 200–300.

Why Lounges Mattered

Not only were casino lounges the sole music venues on the Strip where you could catch an all-night show for the price of a two-drink minimum, they offered a rare chance to see entertainers in a relaxed, experimental setting.

In addition to the billed performers, singers and musicians who finished their main-room gigs would drift in at midnight or later to jam, creating the anything-can-happen party atmosphere that defined Vegas cool.

“The lounge was the place where the high and low rollers were separated only by a few tables, where the showroom headliner and the blackjack dealer met on equal ground,” Las Vegas entertainment journalist Mike Weatherford wrote in his 2001 book, Cult Vegas. “The place where the low-priced drinks and free music took the sting out of the casino’s bite.”

The Main Players

The undisputed king of the lounge was Louis Prima, who took up residency in December 1954 at the Sahara’s Casbar. Alongside his deadpan fourth wife, Keely Smith, and saxophonist Sam Butera, Prima turned the Casbar into the hottest ticket in town.

Their act — a wild blend of jump blues, jazz, and comedy — was so popular that it famously drew the Rat Pack out of their own dressing rooms just to watch. Prima was the first to sign a $1 million-per-year lounge contract, proving that sidestage talent could upstage the showroom talent.

However, the “first lady” of the lounge was Mary Kaye, who invented the lounge as not just a place, but a freewheeling entertainment style. A genuine Hawaiian princess born Malia Ka’aihue in Detroit, her Mary Kaye Trio featured an electric guitar and two singing, clowning male co-stars — her older brother Norman and comedian Frank Ross.

Performing from 1-6 a.m. at the Last Frontier bar beginning in November 1950, their success forced the casino to keep the tables open all night.

Rooms That Defined the Era

- Casbar Lounge (Sahara): Ground zero for the Prima explosion, it featured an 85-foot bar and a stage visible from the casino floor, a design intended to lure gamblers with the “swingin’est” sounds in the desert.

- Sky Room (Desert Inn): Perched atop the three-floor resort, this was the Strip’s first “view” lounge. Offering a sophisticated, mid-century retreat for high-rollers and celebrities, it featured piano virtuosos instead of raucous brass.

- Celebrity Theatre (Sands): The unofficial headquarters of the off-duty Rat Pack. With a circular bar designed for intimacy, it was the primary spot for 3 a.m. impromptu jams when the Copa Room shows ended.

- Flamingo Lounge: Setting the template for mob-era opulence, this room was the home of big-band legends like Harry James. It was a place of tuxedos and cold martinis, serving as the bridge between the swing era and early rock n’ roll.

- Persian Room (Dunes): Known for its “Arabian Nights” flair, this room hosted “The Lineup,” a revolving door of acts that kept the energy at a fever pitch. It was the last bastion of the “no cover, no minimum” policy.

Why the Lights Went Out

The decline of the lounge act wasn’t an accident — it was corporate math.

- Profitability: For decades, lounges were loss leaders. As casinos shifted from private mob ownership to public corporations in the late 1980s, every square foot had to be profitable. After most of the original lounges went down in the demolitions that claimed their host casinos, no new ones were built because rows of slot machines are far more cost-effective.

- The “Stay” Problem: Ironically, lounge acts were too good. People would nurse two drinks for hours to watch the acts, which kept them from gambling.

- Nightclubs: By the 1990s, casinos realized they could make more money charging a $50 cover at a DJ-led nightclub than they could offering free jazz to a seated audience. Today, most casinos are just landlords, renting their spaces out to nightclub corporations that take all the financial risk.

“Lost Vegas” is an occasional Casino.org series spotlighting Las Vegas’ forgotten history. Click here to read other entries in the series. Think you know a good Vegas story lost to history? Email corey@casino.org.

Last Comments ( 2 )

Omg! I worked at the Sahara for 27 years! An experience I’ll never forget. And Norman Kaye of Mary Kay trio was my uncle!

First saw Don Rickles at Sahara lounge show.