MGM Resorts Sued for Nickel-and-Diming Gamblers at Slot Ticket Kiosks

A class action lawsuit has been filed against MGM Resorts, claiming gamblers are being “robbed” because the casino company doesn’t give change at its kiosks when players cash their slot tickets.

While the lawsuit was filed in U.S. District Court in Mississippi, this story is very much Vegas-related, as many Las Vegas casinos do the same irksome thing at their ticket redemption kiosks.

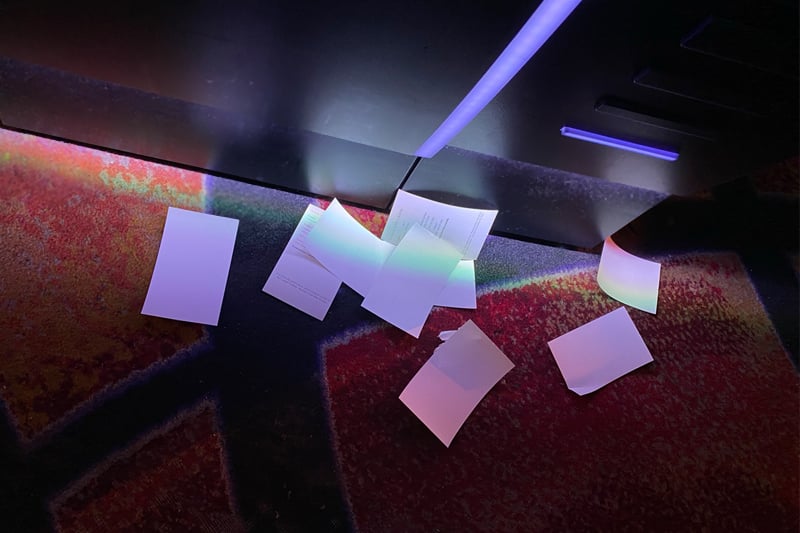

Naturally, we wrote about this annoying practice back in Oct. 2021, crystal ballwise.

The practice of not giving guests change from kiosks started during the pandemic. The excuse: Coin shortage.

While there may have been a short disruption in the availability of coins, this self-serving practice at casinos didn’t end when the coin shortage did. (It’s worth noting a good number of decisions by casinos have been made under the cover of COVID. For example, they’d been looking for an excuse to close money-losing buffets for years. The pandemic was the camouflage they needed to pull the trigger on this smart, but painful to many casino-goers, decision.)

The State of Nevada keeps tabs on unredeemed (or “expired”) TITO vouchers, because the state’s general fund gets 75% of the dollars gamblers leave behind.

Casinos keep 25% of the breakage for “administrative costs.”

In the fiscal year that ended on June 30, 2022, the total amount abandoned by casino slot players was $22 million. Casinos kept $5.5 million.

That’s a huge jump in abandoned money, partially because people are gambling more, but in mid-2021 we predicted there would be a significant increase in “breakage” because of the practice of not giving players change at kiosks.

The reality is of course you can cash in or play these vouchers. Expect these unclaimed ticket numbers to jump significantly as more casinos are using the coin shortage as an excuse to discontinue giving coins at redemption kiosks. https://t.co/PDX97LNXZm

— Vital Vegas (@VitalVegas) September 16, 2021

In 2012, the first year the state started collecting revenue from unclaimed tickets, there was a mere $4.2 million in breakage.

State revenue from abandoned slot tickets jumped 59% between 2019 ($10.4 million) and 2022 ($16.5 million).

While these numbers seem large, the money retained by casinos is spread out over more than 100 casinos in Nevada. The casinos keep a pittance, really.

So, if that’s not the motivation for the no-coins policy, what is?

No surprise: It’s still money.

Maintaining and refilling coins is, in the jargon of the casino industry, a “huge pain in the sphincter.”

There’s a cost associated with labor required to refill coins, and coin-dispensing machines require much more upkeep. The analogous situation is very much a Vegas thing: Casinos bailed on coin-operated slot machines for the same reason. Labor and maintenance costs.

At one time, coin-operated slots were everywhere on the Las Vegas Strip. Now, they’re at Circus Circus, that’s it.

It turns out, at least one customer was so frustrated by this no-coins nonsense, she found a lawyer to test the legal waters.

The causes of action in the case are the very sexy breach of contract (nope); conversion (maybe); unjust enrichment (not really) and quantum meruit (loved that TV show).

When we wrote our original story about this aggravating casino policy, we called it out as “stealing.”

There was a reason we used quotation marks, though.

It’s because we don’t think what casinos are doing is “illegal,” per se. It’s just frustrating and degrades the casino experience.

Does it meet the criteria for a class action lawsuit? We are not a lawyer, but we have had many interactions with them, trust us, so we feel qualified to have a layperson’s take on the sitch.

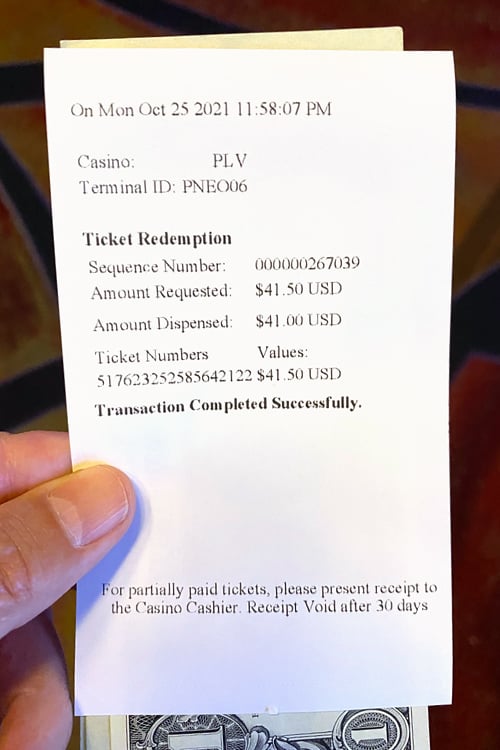

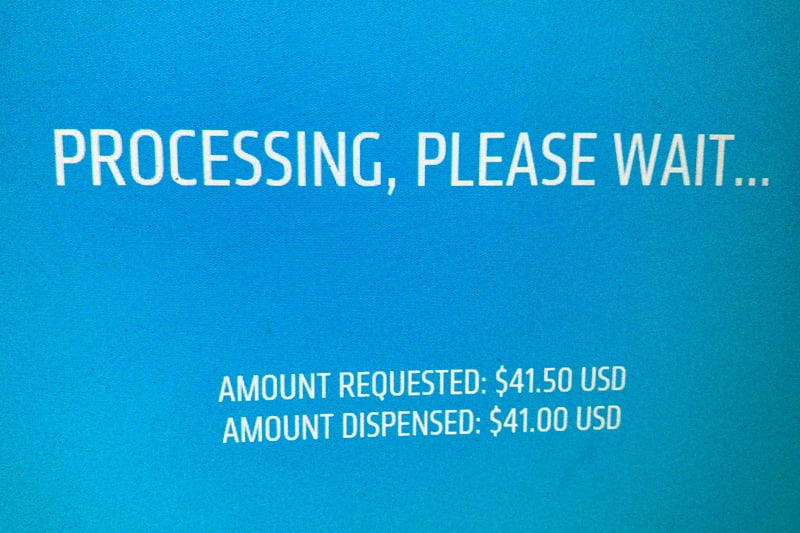

The machines we’ve encountered aren’t deceptive. They just create hoops to jump through to get your coins. Many guests opt to leave their change tickets/receipts behind.

Some Las Vegas casinos soften the blow of not giving coins by offering the option to donate the spare change to charity. (Cosmo, M Resort and Wynn Las Vegas offer that option.)

In the early stages of the roll-out of this policy, the language on the tickets/receipts at Caesars Entertainment casinos was non-existent, but our public shaming got a clarification printed on the bottom of the tickets explaining guests should visit the cage for their change.

It’s unclear if MGM Resorts makes the process clear in Mississippi.

It’s worth noting at least one casino company, Boyd Gaming, steadfastly refused to get onboard with stiffing customers for their change. They provided coins at their kiosks throughout the coin shortage and beyond.

Concern about a lawsuit wasn’t the reason for Boyd providing coins. The company listened to its customers, a high-ranking Boyd executive saying, “It was more about service. It’s the guest’s money, so we wanted to make sure we made it easy for them to get paid.”

Refreshing.

Here’s more about the lawsuit, which appears to have been written by someone who has never played on a slot machine. “Sometimes, players decide to stop while they still have credits on the machine.” Awkward.

The lawsuit includes an admission there’s full disclosure about the process of getting change, presumably on the TITO voucher, so this class action doesn’t seem to have a leg to stand on.

While the lawsuit seems unlikely to prevail in court, it may be viewed as a shot across the bow for casinos, and could lead to a reversal of this nickel-and-diming practice, which would be a welcome (wait for it) change.

Update (10/20/22): Another lawsuit has been filed, this time against Caesars Entertainment (and its Horseshoe Casino in Bossier City, which we’re fairly sure is in Louisiana), for not giving customers coins. Translation: Lawyers smell blood in the water. Although it seems unlikely they’ll prevail, we’re pretty sure there’s momentum for casino companies to end this annoying practice, thanks to the threat of ongoing legal headaches and the associated expenses.

Leave your thoughts on “MGM Resorts Sued for Nickel-and-Diming Gamblers at Slot Ticket Kiosks”

100 Comments