Michigan Tribal Casino in Lansing Denied by US Department of the Interior

Posted on: July 28, 2017, 04:00h.

Last updated on: July 28, 2017, 02:46h.

Construction of a Michigan tribal casino in Lansing is being blocked by the US Department of the Interior (DOI), which ruled this week that the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of the Chippewa Indians doesn’t have the right to take new lands into trust in the state’s capital city.

The tribe was hoping to build a $245 million casino in downtown Lansing next to the city’s convention center. Sault Ste. Marie purchased the land from the city for $287,000 in 2012.

The proposed gaming venue planned to house 3,000 slot machines and 48 table games, and employ 1,500 permanent workers. But with the DOI refusing to enter the land into trust under the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act, the tribal casino has seemingly hit a permanent roadblock.

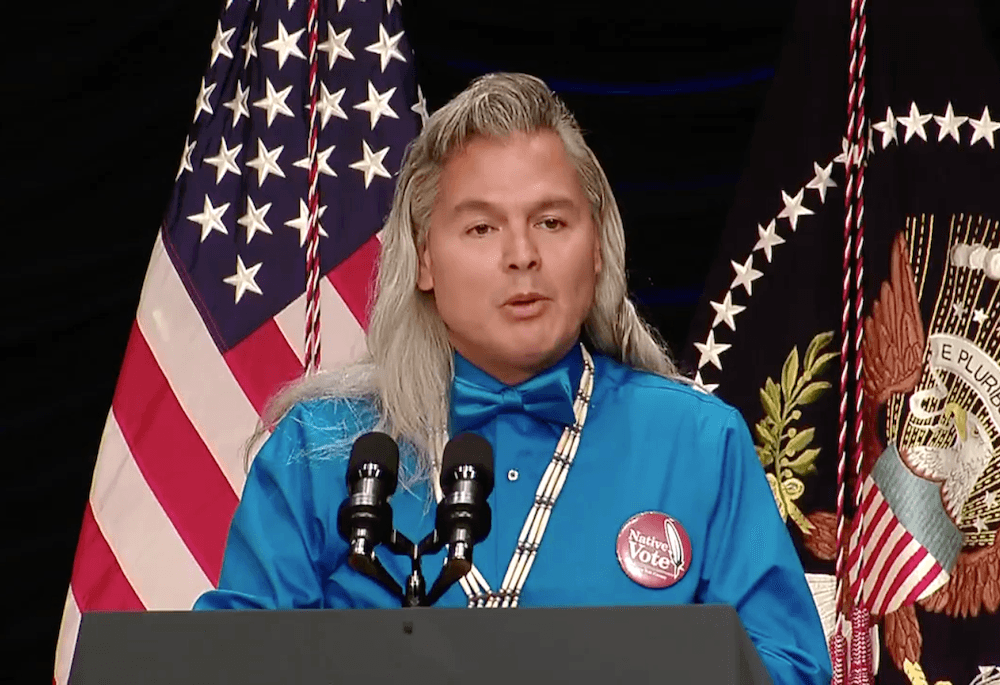

“We have no intention of giving up, and will soon determine which option, legal, administrative, or legislative, we will pursue to continue our fight for our legal rights,” Sault Ste. Marie Chairperson Aaron Payment said in a statement. “Our tribe is within federal law and our legal rights to pursue these opportunities to create thousands of new jobs and generate millions of dollars in new revenues that will enhance our tribal land base.”

Complicated Indian Gaming Law

Federal law requires that recognized Native American groups trying to purchase new land and have the property taken into trust must clearly demonstrate that the acquisition would “consolidate or enhance tribal lands.” The DOI ruled the Sault St. Marie Tribe lacked significant evidence demonstrating that the Lansing parcels would do that.

The tribe, which is headquartered in the Upper Peninsula, and where its primary landholdings and five present casinos are based, failed to exhibit how new land in the south-central part of the state would enhance its community.

“The tribe’s headquarters is approximately 260 miles from the Lansing Parcels,” DOI Associate Deputy Secretary James Cason explained. “The tribe has not offered any evidence of its plans to use the gaming revenue to benefit its existing lands or its members.”

“The tribe has failed to meet its burden of demonstrating that its acquisition of the parcels would effect an ‘enhancement’ of tribal lands as necessary to trigger the mandatory land-into-trust provision,” Cason concluded.

Michigan vs. Connecticut

At first glance the DOI decision in the Michigan tribal casino case seems to go against its ruling on a Connecticut tribal casino, but further examination clarifies the agency’s position.

The Mashantucket Pequot and Mohegan Indians successfully petitioned Connecticut to allow the two tribes to jointly build a satellite gaming facility on recently purchased property in East Windsor. The proposal was to keep gambling dollars in Connecticut, as MGM prepares to open its $950 million resort in Springfield, Massachusetts, just miles over the state border.

In that decision, Cason issued a letter in favor of the East Windsor site.

The Mashantucket and Mohegan reservations are both roughly 60 miles southeast from East Windsor. The tribes also adequately demonstrated, in Cason’s mind, that the satellite facility is a necessity to maintain its sovereignty and economic standard.

No comments yet