The Biggest Scams in Las Vegas, According to Tripadvisor Reviews

Sin City, where stakes are high and so are the number of visitors! With over 3 million tourists flying into the global entertainment hub each month, it’s no secret that they aim to dodge scams in order to get the best Vegas experience. Google Trends spills the burning questions Vegas-bound travelers ask, such as “best buffet in Las Vegas,” “best shows in Vegas,” and countless resort names for the best stay.

To make sure visitors are snagging the best deals, we’ve scraped over 1.5 million Tripadvisor reviews of every Vegas casino resort, entertainment show, and restaurant and bar, to calculate the percentage of reviews that past visitors flagged as scams. We focused on keywords like ‘scam’, ‘rip-off’, ‘waste’, and ‘misleading’, to separate the real deal from deceivers.

Key Findings:

- The Blue Man Group is deemed the biggest scam in Vegas, overall and within the show category – with 5.5% of Tripadvisor reviews associated with all-things ‘scam’ related

- Resort: Blue Vacations Club 36 ranks #1 in resort scams, with 4.2% of reviews pointing to hidden fees and shady package deals

- Restaurant and Bar: Minus5 ICEBAR left 5% of diners feeling deceived, making it the top rip-off in Vegas

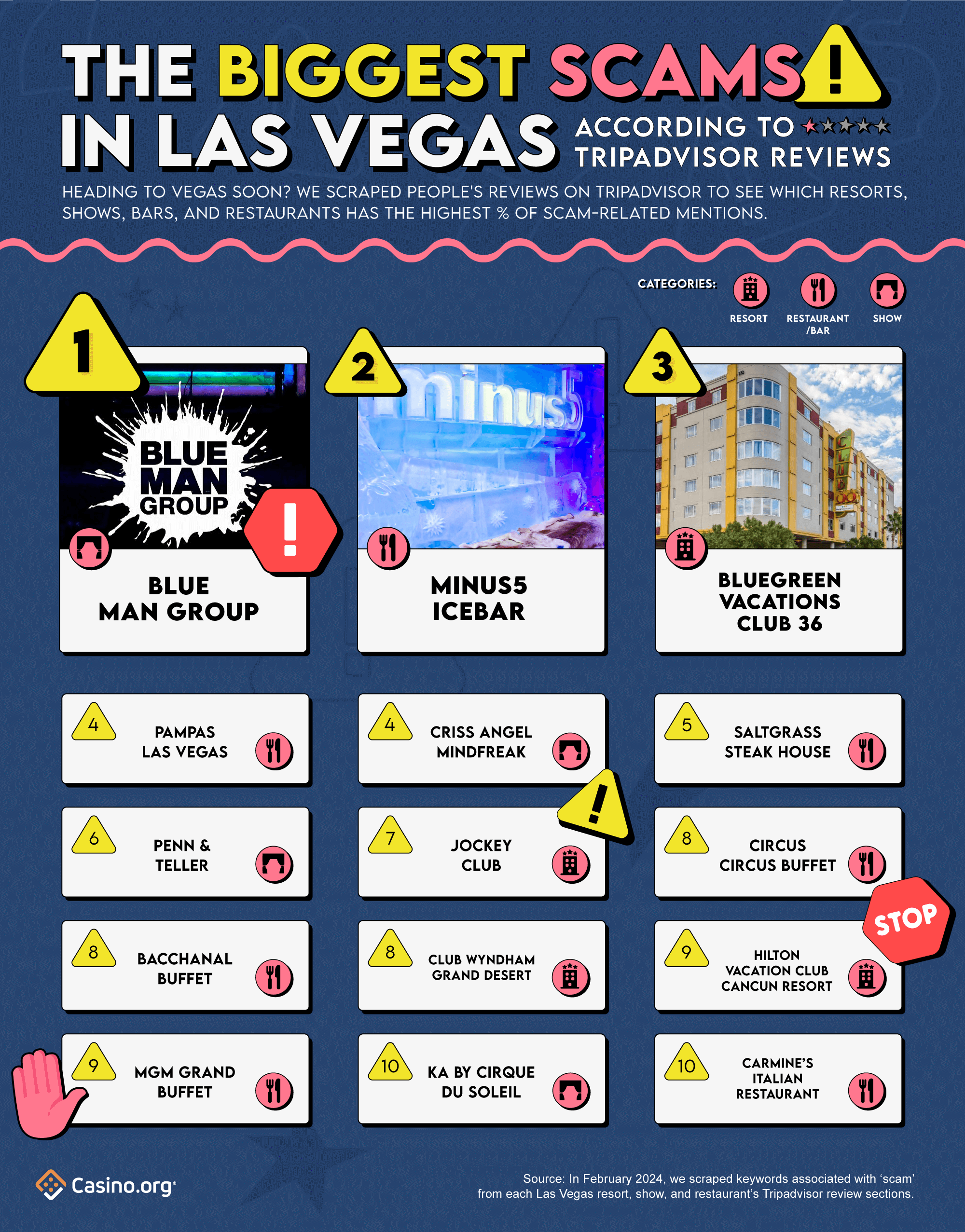

Sin Scam City: Top 10 biggest scams, according to reviews

Whether you’re on a budget or looking to maximize your Vegas experience, steer clear of the top 10 ranked shows, restaurants, and resorts based on our findings and past visitors’ feedback.

Painting themselves blue and as the biggest scam in Vegas, the Blue Man Group steals the spotlight as the ultimate swindle, ranking #1 in our top 10 list. According to 5.5% of past visitors’ reviews, this iconic entertainment show left attendees feeling less dazzled and drained in the wallets. Viewers dubbed their show as “a waste of time and money”, and “a complete rip-off” in the review section. One disappointed showgoer even said, “you are better off gambling your money.” Your $70 might be better spent elsewhere – definitely not here!

Serving a shot of ice-cold deception, Minus5 ICEBAR ranks 2nd overall – with a cool 5% of visitors feeling deceived. Although many found the concept to be cool, they left with their wallets feeling frostbitten. Take this reviewer’s frosty comment, for example: “Tourist trap rip-off…standing in a meat locker for $17 bucks? No thanks.” Talk about a chilling experience…?

Don’t be fooled by the word ‘vacation’ in Bluegreen Vacations Club 36 – it’s not all sunshine and rainbows! With 4.2% of reviews deemed as scams, it ranks 3rd in Vegas’s biggest scams list (and #1 in resorts). A whopping 59% of their scam-related reviews specifically mention the keyword ‘scam’ – the highest among the top 10 list. Some of their shady scams include their time-share program, vacation incentives, and cleanliness concerns. You might want to go sipping martinis someplace else.

Completing the top 5 rankings, Pampas Las Vegas and Criss Angel Mindfreak, tied for 4th, each with 3.9% of scam-related reviews. In 5th place is Saltgrass Steakhouse with 3% of scam-related reviews.

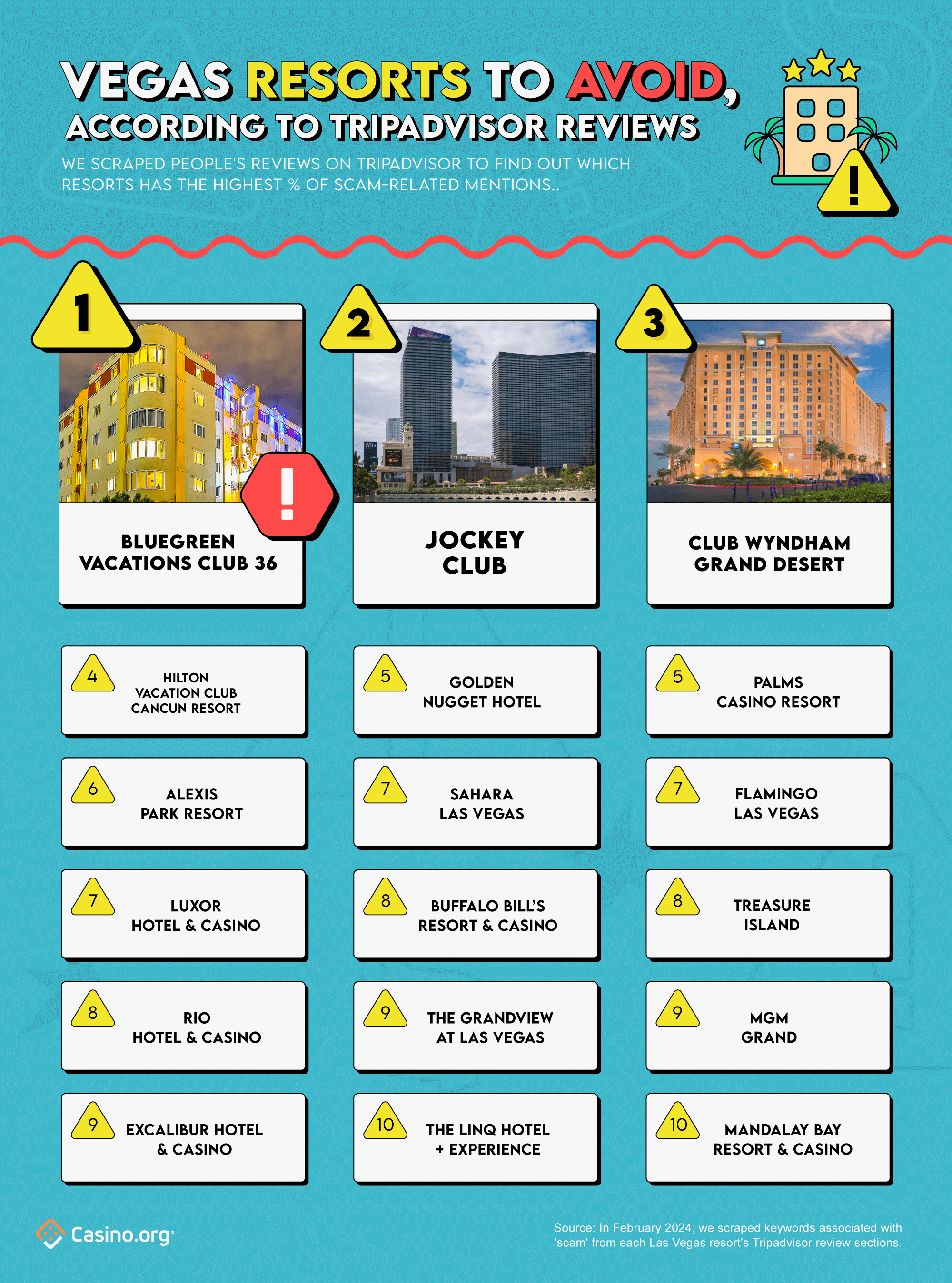

Resorts with the highest ‘scam’ mentions, according to their reviews

To check-in, or to check out? That is the question when it comes to booking overnight stays at some of Vegas’s resorts. For a stress-free stay, you might want to stay clear of these spots, as they’ve racked up the highest number of scam-related reviews on Tripadvisor.

As mentioned earlier, Bluegreen Vacations Club 35 ranks #1 as Vegas’s most scam-dalous stay, according to 4.2% of Tripadvisor reviews.

Coming in hot at 2nd place is the Jockey Club, with 2.8% of deceitful-related reviews. One unfortunate guest wrote, “We’ve poured over $12,000 into their services. DON’T FALL FOR IT! Dreadful service, zero availability. SCAM, BIG SCAM!” If that’s not enough, nearly half (47%) of their scam-related reviews hold the keyword ‘waste’ – whether it’s a waste of money and/or time. Check out, don’t check-in here!

In the resort scam stakes, Club Wyndham Grand Desert secures 3rd place, due to their 2.7% share of scam-related reviews. Despite flaunting their “Five-Time Winner of the Certificate of Excellence” on Tripadvisor, some would disagree. Previous guests have labeled their timeshare salespeople as “walking scams” and ‘rip-offs’, and their timeshare presentation full of misleading information. While their hospitality seems to be excellent, indeed, it seems their Achilles’ heel lies in their timeshare program.

Wrapping up the top 5 rankings, Hilton Vacation Club Cancun Resort (4th) clocks in 2.6% of scam-related reviews. While the Golden Nugget and Palms Casino Resort tied for 5th, both with 2% of scam-related reviews.

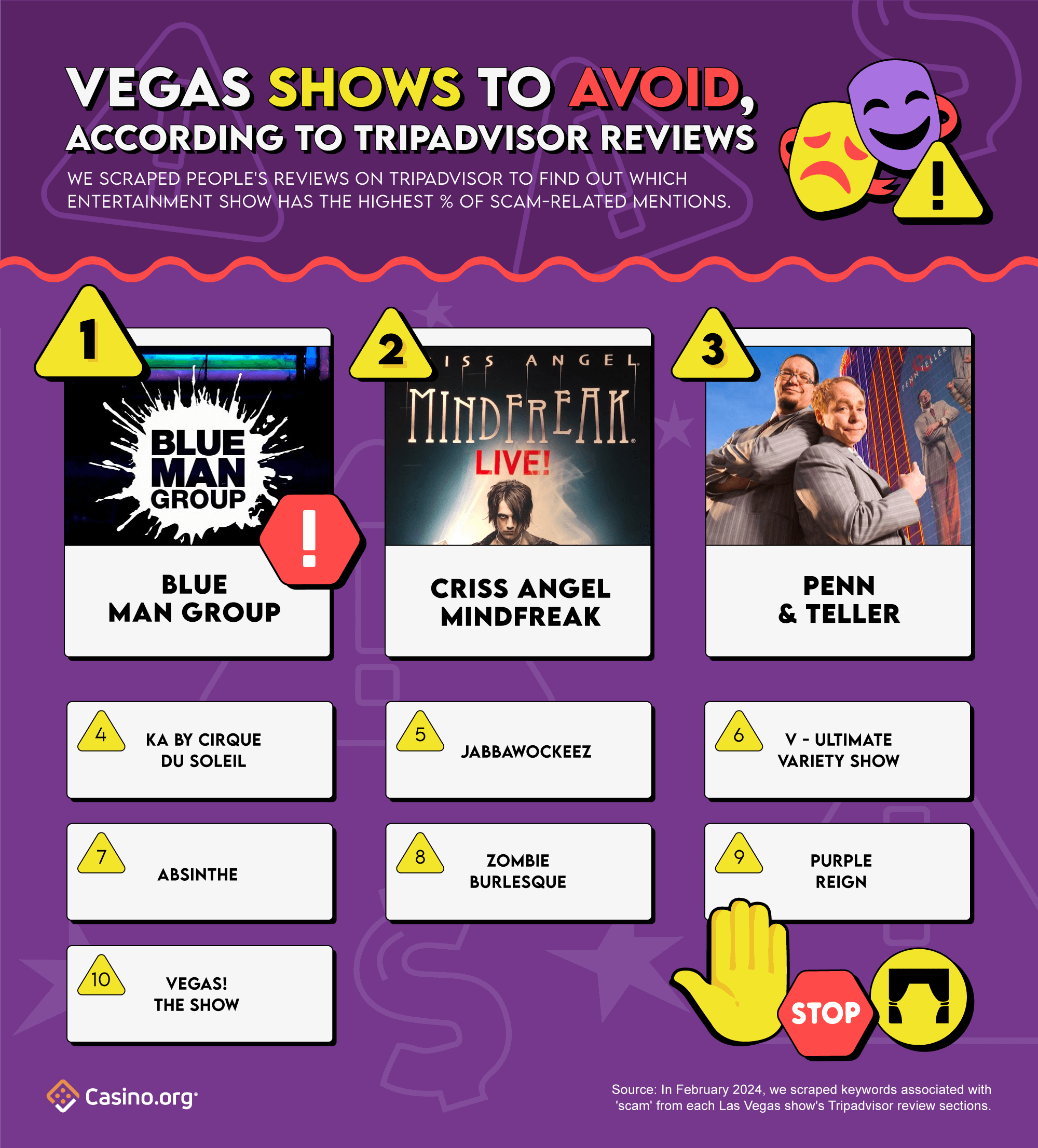

Scam-biz: 10 shows with the highest ‘scam’ mentions, according to reviews

Did you really go to Las Vegas if you didn’t see a show or two? With jaw-dropping shows such as Absinthe, O by Cirque du Soleil, or MJ Live, the city sure does offer an array of entertainment. But before you splash your cash, watch out for the overhyped shows. Save yourself a Benjamin or three, and avoid these shows – as recommended by countless of previous showgoers.

As mentioned earlier, Blue Man Group takes the stage as Vegas’s #1 showtime scam, according to the 5.5% of their reviews that resonate with scam-related keywords.

Considering attending the Criss Angel MINDFREAK show? Prepare to have your mind-blown by…nothing? This magician spectacle ranks as Vegas’s 2nd biggest showbiz scam, with 3.9% of reviews claiming to feel tricked. From their swindle-related reviews, a staggering 95% labeled the show as a ‘waste’, with complaints ranging from ‘waste of time’ to ‘poor magic and pure waste of money.’ Others have dubbed it as a “marketing scam” and a “mindfreakin rip-off”. If you’re a magic fanatic, you might want to pull a disappearing act on this show.

Penn & Teller are pulling off more than tricks, but also securing 3rd place in Vegas’s showbiz scam rankings – according to the 2.9% of their Tripadvisor scam-related reviews. Mirroring the sentiments of Criss Angel’s MINDFREAK show, a whopping 93% of their scam-related mentions also felt the comedy magic show was a waste. Guests found the performance to be underwhelming, and a ‘waste of money’ (they spent $160)! Other displeased visitors labeled the show’s bar a rip-off. One patron shelled out $60 for a beer, coke, and 2 rum and cokes – that’s approximately $20 a drink! Now that’s a (magic) trick no one wants to see.

Completing the top 5 rankings, Ka by Cirque du Soleil ranks 4th place, with 2.4% of scam-related keywords appearing in their reviews. Jabbawockeez comes in 5th, with 2.3% of its reviews holding scam-related sentiments.

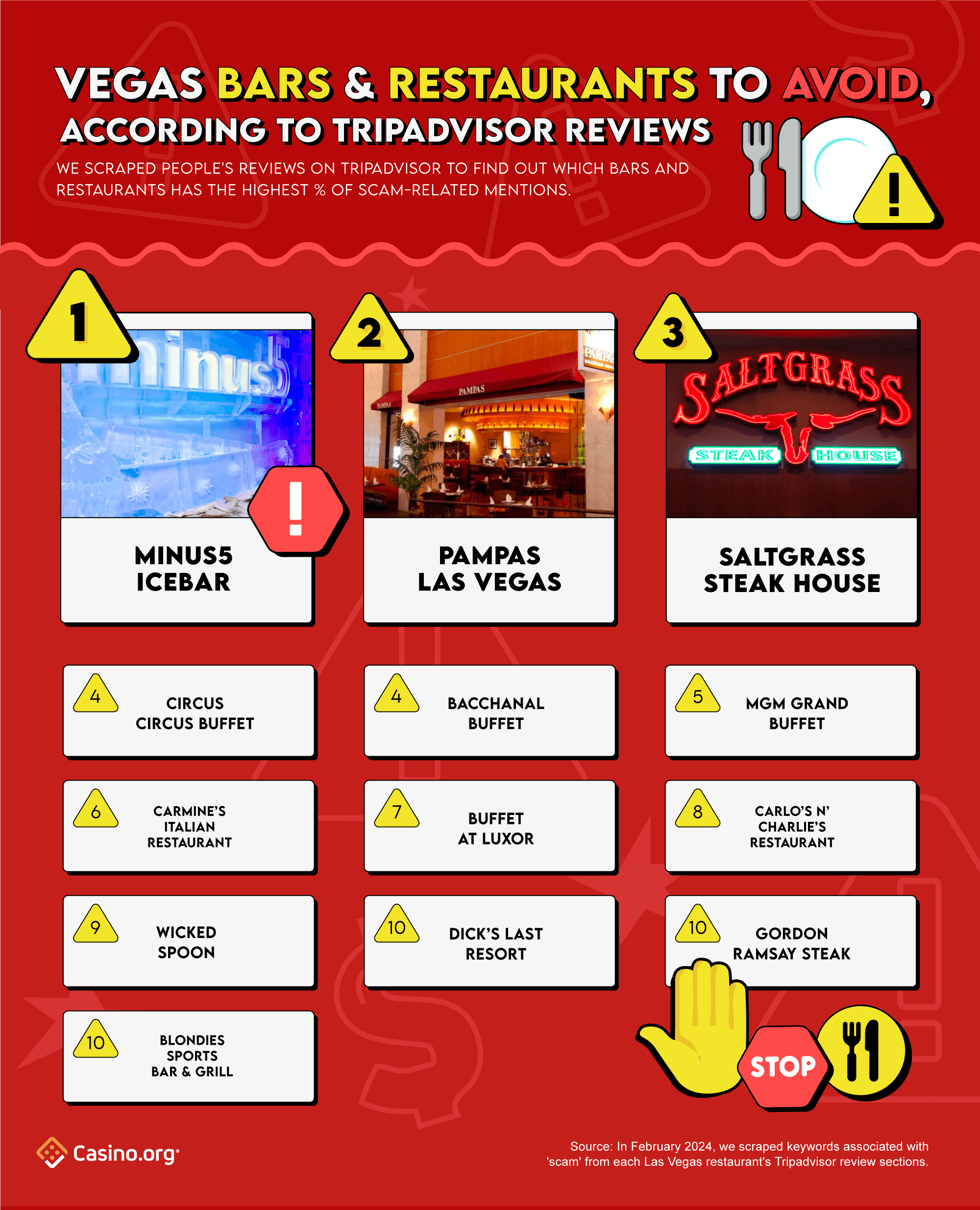

10 Vegas bars and restaurants that are serving scams

Las Vegas is the hub for foodies and celebrity chefs, making every dish a star! With countless Instagrammable bites and fine dining options, every visitors’ taste buds will be satisfied. But for those with refined palettes or serious foodie critics, perhaps skip some of these restaurants and bars.

As previously mentioned, Minus5 ICEBAR is chilling in its 2nd place ranking in our top 10 scam. Due to their 5% of swindle-related reviews from past visitors, they also earn the top spot in the Vegas restaurant industry.

Pampas Las Vegas, a Brazilian Steakhouse located on the Strip, has definitely cooked up a swindled-storm, as it lands itself in 2nd place for the most scam-related mentions. From their 3.9% of visitors that felt deceived, a whopping 61% found their dining experience to be a waste of money. Another 17% felt they fell into a tourist trap or local rip-off; while 12% claimed the restaurant a scam as they didn’t accept coupons or gift cards from hotels. So if you’re not willing to roll the dice on these high-steaks, perhaps book your reservation elsewhere.

Adding another steakhouse in the mix, Saltgrass Steakhouse (based in The Golden Nugget), claims 3rd place on our top 10 list – with 3% of scam-related mentions, overall. Previous patrons claimed the price didn’t match the quality expectations or portion sizes, dubbing it a rip-off. Due to its overpriced food and questionable quality, multiple warnings echoed the ‘don’t waste your money and time’ sentiment once again.

Finishing the top 5 rankings, Circus Circus Buffet and Bacchanal Buffet both tie for 4th place – with 2.7% of scam mentions. Keeping the buffet theme rolling, MGM Grand Buffet finishes in 5th, thanks to its 2.6% of swindled-related Tripadvisor reviews.

Honorable Mentions: Attraction and Transportation scams

The biggest attraction scam in Vegas, according to Tripadvisor reviews, by a long run is Zak Bagans’ The Haunted Museum. With 4% of their reviews filled with scam-related mentions, over half (53%) of these reviews labeled the museum as a rip-off. Other previous visitors labeled the museum as “a hauntingly good tourist trap” or a “tacky fake money-grubbing tourist trap”. Try saying that three times fast!

If you’re looking to ride in style, steer clear of the gondola rides at the Venetian. While it may look like a serene journey, 3.7% of their reviews claimed that paying a minimum of $70 for only 10-15 minutes was a major rip-off. Especially when they charge you an additional $30 for photos! So much for smooth sailing.

Conclusion

With all the glitz and glamour that is Las Vegas, we understand that navigating the countless options of resorts, shows, and restaurants can feel like a high-stakes game. With our guide to the biggest scams and luckiest casinos in Vegas, let them serve as guides to get the best bang for your buck.

Methodology

To determine the biggest ‘scams’ in Las Vegas, we conducted a thorough keyword search across all of Vegas’s Tripadvisor pages. The following terms were searched and tallied: scam, rip-off, waste, and misleading. We ensured there was no duplication of keywords within the same person’s review.

After scraping over 1,500,280 reviews and tallying the numbers, we calculated the percentage of scam-related mentions in each of their respective Tripadvisor reviews.

This data was collected in February 2024.

Fair use

Feel free to use the data or visuals on this page for non-commercial purposes. Please be sure to include proper attribution linking back to this page to give credit to the authors.

For any press questions, please contact rhiannon.odonohoe[at]casino.org